December 11, 2023/in Autumn 2023_#Cycles

by Gert Jan Harkema

The tiny moment of the past grows and opens onto a horizon, at once mobile and uniform in tone, of one or several years… She has the same feeling, alone in the car on the highway, of being taken into the indefinable whole of the world of now, from the closest to the most remote of things. – Annie Ernaux, The Years

Midway through Nomadland,[1] Chloé Zhao’s critically acclaimed 2020 feature where we follow the van-dwelling nomadism of Fern (Frances McDorman) through the seasons of work, life, and capitalism, we watch her on a guided tour through the Badlands National Park in South Dakota. ‘This is gonna be really exciting,’ her tour guide Dave (David Strathairn) – a friend to become romantic interest, tells his listeners. ‘Rub two stones together. And you see what happens as they start to get like sand.’ Fern, meanwhile, wanders off deep into the iconic sandstone landscape. The camera captures her, restlessly wandering, twisting and turning, as if she searches for something hidden in these rocky formations that were the result of deposits 75 million years ago, followed by 500,000 years of erosion. She searches until her friend Dave whistles and shouts from a distance, asking Fern if she found anything interesting. ‘Rocks!’ is Fern’s sole reply. She climbs up and sees the guide as a sole individual contemplating the mountains and a group of tourists regrouping in a following shot.

This scene illustrates Fern’s relation to others, and to the natural surroundings that are so pivotal to the film’s aesthetics. In Nomadland, we feel Fern’s turmoil and trauma through her entanglement with the landscape. A widow who lost both her husband and her place of belonging, we travel with Fern on her nomadic existence through landscapes of melancholy, despair, and hope. She reconnects with people, and leaves them. Or she is left by them. She is half in a group, half on her own; halfway between rebuilding her life while her body (and her van) is deteriorating. Half sand and half stone, somewhere in a cyclicality between the past, a present, and a potential future. Fern’s experience through different cyclical processes of deterioration and resurgence resonate with the deep time temporalities of erosion and uplift.

Fig. 1: Fern surrounded by a sandstone environment in Nomadland.

The landscapes and natural surroundings, together with the human bodies and non-human objects on screen contribute to an aesthetics that contain different temporal dynamics. These natural and anthropogenic landscapes do not just function as setting or scenic background to the narrative. Rather, they appear as temporalised landscapes in which bodies operate and which, in turn, impact Fern’s whole being. Nomadland enacts what it means to perceive what Tim Ingold calls the temporality of the landscape, entailing an embodied engagement with the landscape as ‘an act of remembrance, and remembering not so much a matter of calling up an internal image stored in the mind as of engaging perceptually with an environment that is itself pregnant with the past’.[2] The rock formations and canyons that Fern’s wanderings are situated in are marked by the cyclical dimension of deep time. They move in a temporal width that is far removed from the lifespan of human and non-human animals. Moreover, as temporalised landscapes, these natural environments of forests, sand, and stone appear in stark contrast to the yearly cycles of the seasons, the short-term exhaustion of consumption and consumerism that signify the imagery of the film.

It is in the entanglement with the different cyclical processes of erosion and resurgence that human time and geological time meet in Nomadland. Fern’s personal narrative signifies how the capitalist cyclicality of production and consumption that is essential to the Anthropocene ends up in the exhaustion of the natural and human environment. The infrastructure that used to support her falls away as the village of Empire, a US Gypsum company town, is closed and after her husband dies from sickness. Thereby the film invites an ecocritical reading that takes into account the appearance of various cyclical dimensions and temporalities in landscapes, bodies, and objects.

Despite its independent financing and its use of non-actors in supporting roles, Nomadland became a modest success with audiences in the US while it became an international success with audiences worldwide.[3] Chloé Zhao received the Academy Award for Best Director as well as Best Picture (together with the other producers, including McDormand), and Frances McDormand was praised for her performances as she received the Academy Award for Best Actress. Meanwhile the film was well-received with critics, as it was appreciated as an accessible ‘empathetic, immersive journey’ and ‘achingly beautiful and sad, a profound work of empathy’.[4] The film’s narration is fairly straightforward with a strict chronological narrative structure that is devoid of any flashbacks or flash-forwards. The film’s drama is not organised around moments of crisis, conflict, or resolution; Nomadland rather constitutes an ambient, atmospheric form of drama.

We travel with Fern in her van to different locations in the American West and Midwest. Essentially a road movie drawing on iconography from the Western genre, it is a film about loss, grief, hardship, and reinvention. Critics and scholars were early to recognise the film’s critique of late capitalism while scholarly debates have centered around the representation of precarity and gender, American landscapes and nationalism, and the neoliberal dystopia in Nomadland.[5] With its narrative of a woman living in rural poverty depicting an experience of nomadic precarity, the film has also been placed within the genre of the rural noir, following films like: Wendy and Lucy (Reichardt, 2008), Winter’s Bone(Granik, 2010), Beasts of the Southern Wild (Zeitlin, 2012), and Zhao’s own Songs My Brother Taught Me (2015).[6]

Drawing on the notion of Anthropocene poetics, ‘thick time’, and sacrifice zones, this paper, in turn, seeks to enrich that debate by presenting an ecocinematic reading of the film by taking into account how in Nomadland different forms and ranges of time and cyclicity are imagined and critiqued. Ranging from capitalist hypercyclicity, yearly seasons, animal and object lifecycles, and human lifespans to the cyclical perspective on deep time, the film presents a range of cyclical rhythms and circular motifs. The film’s critical potential thereby reaches beyond environmental concerns into a more existential ecological perspective, as it is found not just in Fern’s spatial wanderings through the sublime natural and cultural landscapes, but also in her exploration and physical engagement with these different forms of cyclical rhythms.

Following the film’s existential ecological perspective, I suggest looking at Nomadland in terms of Anthropocene poetics. Through a temporal multiplicity and a ‘thickening of time’ Fern’s human, corporeal being gets ingrained into geological time, the natural time of seasons, and the time of non-human beings and objects. Fern’s character thereby becomes, in Stacy Alaimo’s words, an ‘immersed enmeshed subject’.[7] The film presents a performance of transcorporeality as it figures how humans are materially enmeshed both spatially and temporally with the physical world. Decentering ‘the human’, Nomadland thereby invites a cinematic Anthropocenic thinking and imagining. It thereby potentially performs a figuration of nomadic subjectivity which, to follow Rosi Braidotti, entails ‘a politically informed image of thought that evokes or expresses an alternative vision of subjectivity’.[8] And, more specifically, that nomadic figuration entails a subject envisioning that is nonunitary and multilayered, and ‘defined by motion in a complex manner that is densely material’.[9] Nomadland, in this sense, is an expression of nomadic thought in the Anthropocene. It is defined by forms of spatiotemporal materiality, multilayeredness, transgression, and ‘thickness’. This paper opens with a discussion on Anthropocene poetics and thick time before moving to an analysis of the different circular temporal dimensions of geological time or deep time – and the time of stones, in relation to human and natural time.

Anthropocene poetics and the thickening of time

In his work on ecocritical poetry, literary scholar David Farrier conceptualises Anthropocene poetics as a set of recurring forms that allow for an Anthropocenic thinking and imagining through poetic structures.[10] Central to this is the concern that in today’s world, humans act in the present upon layers of deep pasts and deep futures, and that thereby both the past and the future co-exist in the present. The Anthropocene entails, as is widely known by now, how humans are embroiled and depending on deep pasts through the use of fossil fuels, while our involvement in the earth creates a geological time of ‘the human’. To follow Dipesh Chakrabarty’s convergence thesis, the Anthropocene concerns the entanglement of human and natural histories.[11] As a critical concept it forces us to rethink time and humankind’s position within the geosphere. The Anthropocene challenges the nature/culture divide by presenting us a hybrid crash between historical scales.[12] Or, as Ben Dibley states, the Anthropocene ‘is the crease of time… the appellation for the folding of radically different temporal scales: the deep time of geology and the rather shorter history of capital’.[13] This contrasting entanglement between deep pasts and capital’s short history forms the exhaustion of resources that characterises our late-capitalist era. As Chakrabarty states, it remains a challenge for the arts and the humanities to think and imagine together, in one picture, the tens of millions of years of geological timescales and the incredibly smaller scales of human and world history.[14]

Anthropocene poetics, in turn, seeks to refocus our attention on the radically different temporal scales that we are intimately involved in. Farrier describes: ‘Anthropocene poetics is, in part, a matter of intersecting orders of difference – fast and slow, great and small, deep and shallow time interacting in and through human action to shape the world that also, in turn, shapes us’.[15] Farrier identifies three subcategories, or three recurring forms or structures in Anthropocene poetics: a poetics of thick time, a poetics of sacrifice zones, and a poetics of kin-making.

Through the thickening of time, Anthropocene poetics entails ‘the capacity to put multiple temporalities and scales within a single frame, to “thicken” the present with an awareness of other times and places’.[16] Thickening time means creating poetic forms and structures through which the different temporal scales, and thereby the different forms of cyclical time, are experienced in the Anthropocene. It enacts a double presence of geological time or deep time, human time and, in turn, humankind’s involvement in deep time, creating a sublime or uncanny contrast of the temporal dimensions of our being.[17] These forms allow us ‘to imagine the complexity and richness of our enfolding with deep-time processes and explore the sensuous and uncanny aspects of how deep time is experienced in the present’.[18]

The notion of thick time originates from the work of Astrida Neimanis and Rachel Loewen Walker. In their effort to reimagine and reframe climate change from a material feminist perspective, they point to ‘the fleshy, damp immediacy of our own embodied existences’ as a way ‘to understand that the weather and the climate are not phenomena “in” which we live at all – where climate would be some natural backdrop to our separate human dramas – but are rather of us, in us, through us’.[19] Thereby they follow Alaimo’s concept of transcorporeality as the ‘enmeshment of the flesh with place’ while expanding this with a temporal perspective.[20] The thickening of time thereby addresses how the past and the future are coexisting in the present inside and outside the human body. Temporality of the human, from a material perspective, reaches before and beyond human life.

It is thus, in Neimanis and Loewen Walker’s words, ‘a transcoporeal stretching between present, future, and past, that foregrounds a nonchronological durationality’.[21] It is the recognition of the present as uneven and multivalent. This is a transcorporeal temporality that, ‘rather than a linear, spatialized one, is necessary to show how singularities (whether a blade of grass, a human, a slab of marble, or a drop of rain) are all constituted by a tick time of contractions, retentions, and expectations of multiple kinds’.[22] Thick time thereby builds upon Deleuze’s sense of the present, as an instant that is thick with the past, ‘a retention of all past experiences in its making of meaning’ and, more particularly, Karan Barad’s notion of ‘spacetimemattering’ as iterative practices in which the past and the future are reworked in phenomena.[23]Such phenomena, then, are human and nonhuman objects. As a poetics for re-imagining and decentering humankind’s position in an Anthropocene world, thick time invites us to think of humans as enmeshed in space and time. It is about our embeddedness in deep time and deep futures while, at the same time, recognising that we make a lasting impact on the deep time of the earth as well as the near past and future of nonhuman nature. An ‘enfolding in geologic intimacy’, as Farrier describes, the thickening of time is about experiencing the ‘geologic becoming’ that we share with non-human organisms and objects.[24]

Nomadic structures from a sacrifice zone

Nomadland is in many ways a film about time and space, and our material becoming in this world-in-formation. As addressed above, it is a road movie that borrows iconography from the Western genre presenting a disillusioned version of the American frontier.[25] Depicting a typical rural noir narrative, the film chronicles the life of Fern and her struggles to engage in meaningful relations with friends and family after losing both her husband and her place of belonging. Thereby it is also set in the itinerant tradition in American independent cinema (from The Grapes of Wrath [Ford, 1940] to Wendy and Lucy [Reichardt, 2008] and American Honey [Arnold, 2016]), where ‘outsiders on the road’ present dystopic critiques of the American Dream.[26]

However, as a tale that figures an exhaustion of subjectivity, and in which the physical and mental states of the character are played out in open, empty spaces, Nomadland also stands in a long tradition of postwar European art cinema. Fern’s wandering through the sandstone formations, for example, mimics iconic scenes from Antonioni’s L’Avventura (1960) where Claudia (Monica Vitti) searches the cliffs after Anna’s (Lea Massari) sudden disappearance. In both instances the dehumanised landscapes signify the extension of the characters’ physical and mental states. There is no distinction between inside and outside, and between objective and subjective, as the landscape and the characters’ bodies are all that we have. In his theorisation on the time-image, Deleuze describes these moments as ‘emptied spaces that might be seen as having absorbed characters and actions’.[27] Like Nomadland, Antonioni’s films are about what comes ‘after’. That is, it is about what comes after the action or after the event. We do not see the dismantling of Fern’s home, nor do we see the disappearance of Anna. The character does not necessarily stir the action, she ‘records rather than reacts’.[28] The camera, in turn, advances autonomously, it has a body on its own through which it registers and moves. In Nomadland, for example, the camera is actually seated in the passenger’s seat of the van, and occasionally it floats around the car. It never takes up Fern’s point of view, but we rather see, move, and travel alongside her. It is the banal and the everyday through which characters like Fern in Nomadland and Claudia in L’Avventura – but also Vittoria (Monica Vitti) in Antonioni’s L’Eclisse – work their way. In the recurring form of the trip/ballad [bal(l)ade] the character is always journeying and meandering. Yet, as Deleuze concludes, despite the physical movement it is time that is out of joint, it is time that becomes the object of presentation. The body in space-time that becomes the ‘developer [révélateur] of time, it shows time through its tirednesses and waitings’.[29]

The narrative of the film is characterised by cyclical movements of departure and return. Its imagery and framing is charged with temporal dimensions belonging to deep time, human time, and Anthropocene time. Nomadland opens with Fern’s final departure from her former hometown as she sells the remainder of her belongings to a friend and rides into the desert. In the opening shots, the viewer is informed about the rapid, six-month dismantling of Empire, Nevada, a US Gypsum company town that was almost completely abandoned and closed after the company mines were dismantled. In better days, the town had its own elementary schools, its own stores, a small airport, and even a golf course. In short, it was a town that people organised their social lives around.

Now, set in snow and abandoned, the town has become a disposable place, a sacrifice zone where exhaustion of the resources has finished. As ‘shadow places of the consumer self’, sacrifice zones are spaces of mass simplification: the world is divided into productive places filled with resources, and emptied locations of waste.[30] These are inherently relational sites that signify the capitalist world-ecology. The sacrifice zone is the final place in a chain of extraction, production, consumption, and waste. Moreover, as Ryan Juskus remarks, the sacrifice zone has an almost religious connotation: between life and death, certain designated spaces with all the human and nonhuman lives that are lived in these places, are sacrificed as if it were for the ‘greater good’.[31] Fern’s nomadism is the direct result of this sacrifice.

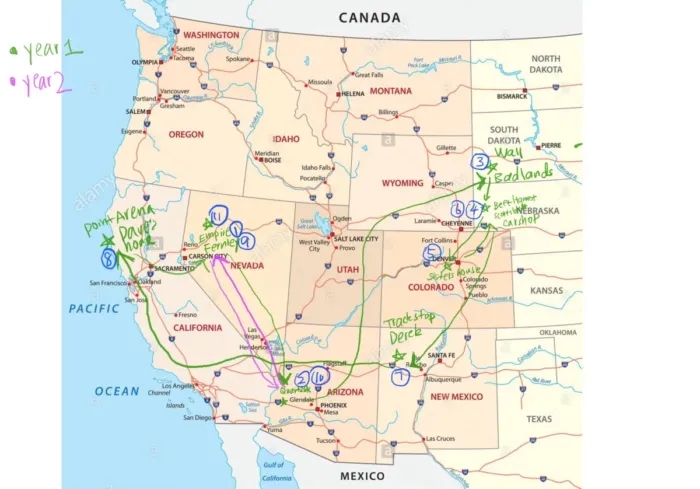

Fern’s circular travels start when she packs up her van with stuff from a storage space. Throughout the film, we see her travelling from one workplace to another. Fern joins Amazon’s ‘CamperForce’, a program aimed to attract the ‘nomadic retiree army’ as a workforce during the holiday season.[32] After a visit to the Rubber Tramp Rendevouz, a social camp for beginning van dwellers, she works in the spring and summer as a host at a campsite near the Badlands National Park in South Dakota before she is employed at the Wall Drug restaurant. Subsequently she takes a job at the beet harvest in Nebraska before she joins Amazon with its CamperForce again. In between, Fern stays at Dave’s place in California where she tries unsuccessfully to settle in. Afterwards, she travels to her sister’s place in California, before she returns in the final scene to Empire.

Fig. 2: Production map provided to sound engineer Sergio Díaz by Chloé Zhao. Source: https://aframe.oscars.org/news/post/creating-the-soundscape-for-nomadland.

Fern’s nomadism is circular. She visits the workplaces as seasonally assembled contact points, gateways on a recurring trajectory. This circular nomadic trajectory has an annual repetition as Fern follows the seasons that, in this case, are not just given by nature but by the capitalist cycles of production and consumption. It follows peripheral places remote from the permanent settlement in the cities and suburbs. Amazon’s gigantic warehouse is a stowaway late-capitalist consumerism. The Badlands campsite and the Wall Drug restaurant are places where tourists pass through but never stay. These peripheral places appear in stark contrast to the Denver suburbs where her sister lives.

Fern is a tribe of one, performing what Édouard Glissant calls circular nomadism. Circular nomadism is contrasted to arrowlike or invader nomadism. After a territory is exhausted, the group of people moves further, producing tracks of familiar places.[33] The survival of the group, as Glissant explains, depends upon their recognition of the circularity, both of their travels and of the land or forests. Yet in the view of history, circular nomadism could be considered ‘endogenous and without a future’.[34] There is no growth and no conquest. ‘“Stationary process”, a station as process’, as Deleuze and Guattari write in their treatise on nomadology.[35] Circularity, in this sense, means conserving and maintaining oneself, making the periphery into the temporary center. The film’s circular nomadism is marked by this process of regeneration. Following Deleuze and Gauttari, this is a nomadism that is profoundly defined by deterritorialisation. There are familiar paths and places and recurring points. But there is no reterritorialisation, there is no new belonging, no ownership and no fixed center of existence or identity.

However, whereas the nomad in Deleuze and Gauttari’s political figuration is dispersed in open or smooth space, the emptied space of Fern’s nomadic travels is striated by forces of capitalist production and consumption.[36] Travelling from one temporary job to another, her life is organised around the conservation of bare life in the face of erosion and exhaustion. We see her working and maintaining, from one point to another, through fatigue and waiting. The filmic landscapes, meanwhile, are striated by roads, railroads, unity poles, camper parks, and production plants. In the smooth-striated space of nomadism, Fern’s gender as a woman, and particularly as a childless middle-aged white formerly middle-class widow, is of course crucial. Her (circular) nomadic subjectivity is socially structured by all these elements. It is this position that allows her a locality and a trajectory as long as there is still some productivity and mobility left in her. Subsequently, the communal element of circular nomadism in late capitalism is constantly renegotiated as Fern befriends and teams up with others, or as she has to leave after the work is done.

This circular nomadism is depicted by altering landscapes and changing weather conditions. After Fern leaves Empire in the snow, she suffers some cold and harsh conditions during and after the holiday season job at Amazon. There is a spring in Arizona, and a summer season in North Dakota, and a stormy autumn at the cliffs of Point Arena in California. Through meteorological displays of the seasons the film develops its rhythm of travels and returns. This is played out in a dichotomy of distant, contemplative long shots of open spaces of lands and skies, and visceral close-ups of bodies, hands, faces, and skin. A combination of montage and duration, accompanied with ambient soundscapes of rain, wind, and thunder, and Einaudi’s atmospheric soundtrack, renders time as a tangible force. Time and movement are presented as a ‘dwelling in the weather-world’ in which the changing conditions of the world become part of our own existence.[37] The weathered landscapes that accompany Fern’s travels, and the recurring images of transit and return open up the film’s poetic dimensions to engage critically with the exhausting rhythms of capitalism and the Anthropocene.[38]

A poetics of thick time

The weathered landscapes that structure the narrative of circular nomadism in Nomadland initiate a thickening of time in several directions, ranging from deep or geological time to human time and the ecological life-cycles of animals and nonhuman nature. Erosion and regeneration appear as recurring motifs in these Anthropocene poetics. Probably the film’s most evident temporal layer is human time. In Nomadland human time is organised around shared experiences of loss, grief, trauma, recovering, and reproduction. Fern, as mentioned, has lost her husband as well as her place of belonging. Swankie (Charlene Swankie), who Fern befriends at the van dwellers meetup in the dessert, faces death herself as she suffers from cancer. Eventually passing away, she is collectively mourned at the Rubber Tramp Rendevouz the following year. Bob Wells, the real-life van-dwelling guru behind the Rendevouz, commemorates his son’s suicide. Bob’s quiet depiction of grief, taken from his real-life experience as a non-actor, reinforces this moment as a point of emotional gravity.

Through the collective sharing of grief, death is presented as existentially part of human life. Concurrently, birth and the arrival of new life adds to these melancholic dimensions in Nomadland. This is most evidently represented by Dave reconnecting with his children with the birth of his grandchild. By way of this interplay of life and death, the human life cycle forms an object of contemplation for the film. At the same time, Dave’s family life is contrasted to Fern’s nomadic subject position as a childless widow. The trauma of life and death shows that whereas all humans share in the experience of a human time, there is a different social location and a trajectory depending on subject positions like gender, class, age, and economic productive potential.

The life cycle of non-human animals appears in Nomadland in arrangement with that of humans. The film thereby presents a thickened image of human time existing concurrently with nonhuman life cycles. The connection between life and death is visualised explicitly through the crosscutting of a shot of living ducks on Dave’s farm which is immediately followed by a close-up of a cooked turkey on the table. Swankie’s death from cancer is heralded by her last video in which she recorded an endless amount of eggshells floating around a swallows colony. Fern, meanwhile, on her way through the woods, recognises herself in a wandering lone buffalo, or she contemplates life watching birds at the cliffs. The reassuring suggestion in this interplay of human and nonhuman life versus death is that all life on earth is involved in circular ecologies reaching beyond individuality.

Drawing on the work of environmental philosopher Thom van Dooren, David Farrier describes this as a poetics of kinship located in the Anthropocene aesthetics. This kinship is about recognising, in the face of exhaustion and extinction, the human and nonhuman other as beings with whom we share our existence as temporal beings. Human and nonhuman animals share an existence and interdependence in what Van Dooren conceptualises as ‘flight ways’. Any individual being is ‘a single knot in an emergent lineage’.[39] Van Dooren continues:

What is tied together is not ‘the past’ and ‘the future’ as abstract horizons, but as real embodied generations – ancestors and descendants – in rich but imperfect relationships of inheritance, nourishment, and care. These are knots of time in time – what Debora Bird Rose has called ‘knots of embodied time’.[40]

The alignment of human and nonhuman cycles of life and death, of Swankie’s passing away with the swallow’s breeding and birth, and the different intergenerational connections about nurture, care, death, and new life, then, needs to be read as an enactment of this embodied time – of ‘knots of time in time’. Meanwhile, in terms of the thickening of time and the multiplicity of temporal dimensions, this lineage of knots of embodied time also functions as a stretching of time into the future, reaching beyond the lifetime perspective of Fern and her friends; and thereby inviting the audience to imagine an existence embedded in time’s pastness and futures.

The landscapes in Nomadland present a temporal multiplicity that also reaches far beyond human and natural life cycles. The natural landscapes play a fundamental role to the poetic film form by contrasting a temporal scale of deep time to the short life cycles of human and nonhuman animals. In its cinematic form these open spaces are presented as ‘intentional landscapes’ that invite the viewer not just to interpret them but also to engage with the temporalised affective environment as a medium that we live in.[41] The long takes with slow (forward) camera movement emphasise duration.

By way of Fern’s engagement with the environment and its open spaces, the film invites what Timothy Ingold calls a ‘dwelling perspective’. This is a mode of remembrance and of ‘engaging perceptually with an environment that is itself pregnant with the past’.[42] In a montage of distant landscape imagery together with close-ups of Fern’s tactile engagement with the environment, the film stresses the materiality of the landscape as a place where the past and the present meet. Through this nomadic dwelling in forests and desserts, the different temporal layers of the past surface in a dynamic interrelation with the present.

Through these landscapes, human time gets interrelated to geological dimensions of time. These scenes appear as landscapes modeled by millions of years of cyclical processes of erosion, tectonic uplift, and regeneration. This deep time circularity then presents a dynamic parallel between humans, nonhuman nature, and geological earthy formations. In Nomadland we travel from the desert and the Petrified Forest in Arizona to age-old redwoods and green forests in San Bernadino; and we move with Fern to cliffs of Point Arena in Northern California to the Badlands in South Dakota. These are iconic landscapes filled with rocks, mountains, cliffs, oceans, canyons, and woods from ancient times. These landscapes that are the object of Fern’s contemplation and embodied engagement are geological terrains caught in the endless cyclical motions of erosion, deposition, and uplift. Dwelling in these temporalised landscapes seems to affirm James Hutton’s eighteenth-century discovery of deep time. That is, the earth as a machine with ‘no vestige of a beginning, – no prospect of an end’.[43]

The South Dakota Badlands sandstone scenery that features prominently in Nomadland presents such a deep time perspective. As a landscape that is forever caught in slow motion, it exposes different geological layers, also known as strata, from between 75 million and 500,000 years ago. These strata are resurfacing due to erosion by the water of the river, the wind and air, and due to the upward movements of the earth and its forces and tectonic drifts. It is filled with what is known as angular unconformities. These unconformities mark temporal gaps between different rock units from different eras. Throughout the film we see Fern walking through, or dwelling in, these open spaces where she touches and feels the rocky formations from other times. It presents a tactile engagement with deep time’s cyclical presence in the present.

Sand, stone, and stars

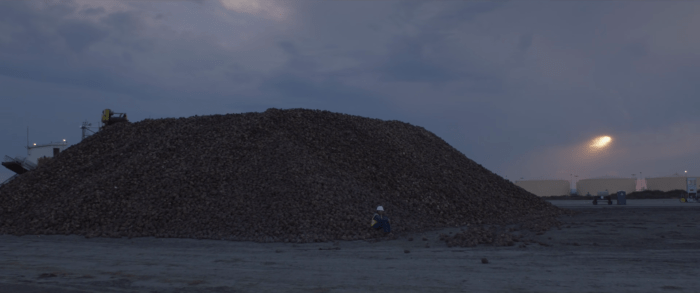

As a poetics of thick time, Nomadland contrasts the deep time natural environments to the landscapes of the Anthropocene. The Anthropocenic formations graphically match geological sites. The locations of capital production are repeatedly shot as if they were natural scenes. In a shot at the beet harvest, for example, we see Fern contemplating in solitude next to what looks like a mountain of beets (Fig. 3). In a similar vein, the Amazon warehouse look corresponds to a canyon (Fig. 4); and the empty and abandoned gypsum mine in Empire now stands in the landscape as a solid rock formation (Fig. 5). Yet what is striking, of course, is that these locations all have a particular (seasonal or abandoned) temporality to them that is completely different from the natural landscapes of the Badlands and the Petrified Forest in Arizona.

Fig. 3: Beet harvest in Nebraska.

Fig. 4: Amazon warehouse as a canyon.

Fig. 5: The US Gypsum mine as rock formation.

In these poetics of thick time, stones and rocks appear throughout the film as material mediations between human time and deep time. Stones, rocks, and pebbles are omnipresent in the film. The hardness of stone often appears in relation to the softness of human bodies and skins. Fern, for example, briefly works at a stone and mineral store in Arizona; and we see her repeatedly touching and brushing collection rocks. Her love for stones is shared by her friend Swankie, who turns out to be an avid stone and mineral collector. When Swankie passes, the van dwellers throw stones into a fire in a memorial service. Like the temporal landscapes from deep time, this involvement with stones affirms Fern’s being in time and a being of time.

Fig. 6: Physical entanglements with stone.

Stone has a temporality far beyond that of humans; its duration is inhuman, as Jeffrey Cohen writes in Stone: An Ecology of the Inhuman. Every stone or every rock is the product of a trajectory through time and space. Stones have their own time, forever in motion they are ‘products of ongoing and restless forces that effloresce into enduring forms, worlds wrought with stone’.[44] Through Fern we recognise this restlessness of rocks in the film. Shaped by geological dimensions of time beyond human imagination, the stones in Nomadland are found, picked up, collected, shared, and then deserted. At the same time, the longevity of these stones contrasts to the short-term nature of the experience of touching them through our hands. Reaching into a past far beyond all human existence, and likely surviving the human species, they speak to another dimension of time. As Cohen writes:

Because of its exceptional durability, stone is time’s most tangible conveyor. Stone hurts, and not just because rocks so easily become hurled weapons. Geologic scale diminishes the human. Yet expansive diversity of strata, some jolted into unconformity through gyred forces and tectonic drift, is almost impossible to comprehend without arrangement along a human calendar.[45]

For most people, as Cohen concludes, the potential alien intimacy that stones present us, the intimacy of a haptic and embodied involvement with a time beyond human time, will remain unnoticed. Yet in her existential crisis of grief and exhaustion, it is this intimacy with other temporal dimensions that Fern seeks.

The intimacy with different temporal dimensions is presumably most explicitly discussed where the film relates human corporeality to cosmic cycles of matter and time. During their work stay at the Badlands campsite, Fern and Dave go star watching. The local guide explains:

Straight up overhead, that’s the star Vega. But it’s 24 lightyears away. What that means is that the light that you’re looking at left Vega in 1987. And it just got here.

The physical and embodied persistence of the past in the present is highlighted when the amateur astronomer continues to note that:

Stars blow up and they shoot plasma and atoms out into space. Sometimes these land on earth. [They] nurse the soil, and they become part of you. So take your right hand, and look at a star. There are atoms from stars that blew up eons ago on this planet, and now they’re in your hand.

This cosmic romanticism is followed by a hard cut to a shot where we see Fern’s hand in close-up cleaning ketchup at the restaurant where she works. Thus the film sets up a poetic relation of stardust between distant cosmic pasts and a present, visceral, and romantic experience of stargazing. But the romanticism and melancholy of that realisation is cut short by swiftly moving to the harsh reality of physical labor for production and consumption in the present.

A transcorporeal stretching of time, or the body as a sacrifice zone

In the film’s Anthropocene poetics the different cyclical dimensions of deep time, cosmic time, and human and nonhuman time is put in relation with the short cycles of capitalist consumption and production. In its narrative of circular nomadism and its political figuration of nomadism, the film puts these multiple scales within one larger frame of reference. The film does not explicitly problematise these relations; it seems to have a modest environmental agenda. Yet through its poetics of thick time, it presents an image of thought on how these different cyclical movements operate on each other. And it proposes an existential ecological critique by outlining how the cyclical short term nature of production and consumption in capitalism, systems that used to support Fern’s individual social life, now exhaust both the earth and its people. Thereby both human and nonhuman beings share in the experience of erosion.

As a figuration of nomadic subjectivity in the Anthropocene, Fern can be seen as the main contact point between these different temporal dimensions. Slowly, the cyclicality of human life wears down on her as well as on the individuals around her. This exhaustion is both physical and mental; and, above all, it is an embodied experience. Throughout the film we see Fern’s body getting older. The movement, the seasons, the work, the people that came into her life and the ones who left, the weather with its sun, rain, cold, and wind all had their impact. It is Fern’s female body that is the site of human time, and of the exhaustion of work, travel, and engagement. We see her body repeatedly in (extreme) close-up, when it rests, or washing the dust off of it when she showers. Left on her own, at the periphery of society, with no children or family to nurture, and outside the loop of social reproduction and capitalist consumption, we can theorise Fern’s body as a sacrifice zone in itself. Up to a certain extent, this seems like a voluntary solitude. Fern is repeatedly asked to rejoin the social life of friends and family, and to settle for a ‘normal’ life or ‘the good life’, most notably on her visit to her sister in the Colorado suburbs. Yet she seems to turn to nature in order to embrace her own position as a temporal being.

Fig. 7: Nomadland.

Fig. 8: Nomadland.

Despite her antisocial and seemingly detached appearance throughout most of the film, Fern’s body is anything but closed off from the physical and social environments surrounding her. It is open in its rhythms and sensibilities, and it is entangled with the surrounding more-than-human worlds and temporalities. It is this shared resonance of different temporal scales that forms the poetics of Nomadland as the ‘transcorporeal stretching of thick time’.[46] Here, trans-corporeality, as Stacy Alaimo writes, entails a ‘literal contact zone between human corporeality and more-than-human nature… [marking] the time-space where human corporeality, in all its material fleshiness, is inseparable from “nature” or “environment”’.[47] As Alaimo stresses, ‘trans-corporeality means that all creatures, as embodied beings, are intermeshed with the dynamic, material world, which crosses through them, transforms them, and is transformed by them’.[48] The physical environments have affected Fern, and Fern’s existence affects the environment. She shares in the world. First in the form of Empire, the abandoned ‘sacrifice zone’, but also elements and the seasons. Fern’s body and subjectivity therefore is figured as transcorporeally enmeshed with the physical spaces of Anthropocene exhaustion.

Nomadland performs precisely how Fern’s transcorporeal being is involved with a temporal frame that is thick and marked by dynamic cyclical movements. Neimanis and Loewen describe this as ‘weathering’, a way of reimaging the body as an archive of the conditions of the world that is stored within the body, and that constitutes the body. A transcorporeal temporality, then, is one of duration, ‘constituted by a tick time of contractions, retentions, and expectations of multiple kinds’.[49] This embodied involvement with the world is also, to repeat Van Dooren’s words, an involvement in ‘knots of embodied time (…) in and of time’.[50] Or, as Neimanis and Loewen Walker point out, transcorporeality also involves a temporal ‘entanglement with a dynamic system of forces and flows.’[51]

Throughout the film we see that Fern gets reinscribed into nature, and into its geological temporalities of deep time and nonhuman time. There are moments in the film when Fern almost becomes part of the landscape, when she turns into a rock herself. Floating in the river, her body appears as a natural object from a different temporal dimension. Nomadland draws upon familiar imagery of the natural sublime reaching back to nineteenth century Romanticism. But different from the subjects in these paintings, Fern is not threatened by it nor is she situated (morally or ethically) above or outside nature. On the contrary, she floats in a stream of water, or at another time almost disappears into the landscape.

Fern’s nomadic subjectivity is in terms of transcorporeality presented as a body journeying through time and space that has become the site of exhaustion. And her body is involved in other cyclical temporalities beyond that of her own.Conceptualising Fern’s being as an embodied sacrifice zone, it is the lack of expectations that marks her trajectory. Devoid of a plan or a prospect, any future seems missing. This transcorporeal stretching is multidirectional. Humans are affected by their environments, and non-human environments are fundamentally changed by human presence. In Anthropocene times, our involvement with the natural and geologic world reaches far beyond the human lifespan. This is a capitalist-driven exhaustion in which both humans, non-humans, and the environment share.

The decentering of ‘the human’, I would argue, is the political figuration of nomadic subjectivity in Nomadland. As a form of ecocinema, the film enables an image of thought that presents us a transcorporeal and material subject position. Rather than celebrating the mobility, freedom, and individualism that so often accompanies the road movie genre, it allows for a conceptualisation of subjectivity that is stretched in temporality and transgresses the individual human body. And, moreover, we can read Fern as a performance of a nonlinear and nonunitary vision of the subject, that is not essentially defined but constantly ‘weathers’ in the world.[52]

Fig. 9: Nomadland, final scene.

Conclusion

Nomadland, I argue, allows for an ecocinematic image of thought about our temporal being in the Anthropocene. It does so by presenting a figuration of nomadic subjectivity in a dynamic framework of different temporalities, resulting in a cinematic poetics of thick time. The cyclical multiplicity in Nomadland occurs through an affective enmeshment of deep time, human time, and many layers in-between. Through an interplay of distant, contemplative, slow-moving scenery shots and intimate close-ups of an embodied engagement with social and natural environments, Fern is situated as a subject within a world-in-formation. The film also critically acknowledges being as enmeshed with our spatial and temporal environment. Nomadism in Nomadland is figured as the end stage of late-capitalism; an endless exhaustive journey.

At the end of the film Fern returns to Empire once more. The film thus ends at the beginning. Searching for her lost life, recollecting her memories, she wanders through the emptied streets and along the gypsum mine. Devoid of social life, these places now appear as ruins that have become part of the natural landscape. The narrative closure is remarkable here. Putting this scene in conversation with the closing shot of John Ford’s western The Searchers, Tjalling Valdés Olmos describes this as Zhao’s way to envision ‘the US West as a hinterland determinately haunted by the afterlives of the frontier’.[53] It is the afterlife of production, the shadow place of geological and human exhaustion. For a brief moment, it seems as if Fern contemplates staying in this sacrifice zone. This is a place where she might belong, where her husband and her social life once was. Wandering at the outskirts of society it mirrors where she is socially situated. Yet, Fern pauses and steps out of this human-house frame, and walks into nature. We see one more shot of her on the road, following her van along the snowy landscape of Nevada. Bereft of home and belonging, there is no end to her nomadic journeying.

Author

Gert Jan Harkema is lecturer in film studies at the Department of Media Studies at University of Amsterdam. His research focuses on relational aesthetics of precarity and on aesthetic experience in film history.

References

Alaimo, S. ‘Trans-corporeal Feminisms and the Ethical Space of Nature’ in Material feminisms, edited by S. Alaimo and S.J. Hekman. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2008: 237-264.

_____. Exposed: Environmental politics and pleasures in posthuman times. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2016.

Barad, K. Meeting the universe halfway: Quantum physics and the entanglement of matter and meaning. Durham-London: Duke University Press, 2007.

Berleant, A. Aesthetics and environment: Variations on a theme. London-New York: Routledge, 2005.

Braidotti, R. Nomadic subjects. New York: Columbia University Press, 2011a.

_____. Nomadic theory: The portable Rosi Braidotti. New York: Columbia University Press, 2011b.

Bruder, J. ‘Meet the CamperForce, Amazon’s Nomadic Retiree Army’, Wired, 14 September: https://www.wired.com/story/meet-camperforce-amazons-nomadic-retiree-army/.

Chakrabarty, D. ‘The Climate of History: Four Theses’, Critical Inquiry, vol. 35, no. 2, Winter 2009: 197-222.

_____. ‘Anthropocene Time’, History & Theory, vol. 57, no. 1, March 2018: 5-32.

Cohen, J.J. Stone: An ecology of the inhuman. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2015.

Deleuze, G. Cinema 2: The time-image, translated by H. Tomlinson and R. Galeta. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1989 (orig. in 1985).

Deleuze, G. and F. Gauttari. A thousand plateaus: Capitalism and schizophrenia, translated by Massumi. Minneapolis-London: University of Minnesota Press, 1987.

Dibley, B. ‘“The Shape of Things to Come”: Seven Theses on the Anthropocene and Attachment’, Australian Humanities Review, no. 52, May 2012: 139-150.

Farrier, D. Anthropocene aesthetics: Deep time, sacrifice zones, and extinction. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2019.

Glissant, É. Poetics of relation, translated by B. Wing. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1997 (orig. in 1990).

Gould, S.J. Time’s arrow, time’s cycle: Myth and metaphor in the discovery of geological time. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1987.

Grønstadt, A. ‘Nomadland, Neoliberalism and the Microdystopic’ in Microdystopias: Aesthetics and ideologies in a broken moment, edited by A. Grønstadt and L.M. Johannessen. London: Lexington, 2022: 119-132.

Holmes, L., Thompson, S., Harris, A., and Weldon, G. Pop culture happy hour, NPR, 19 February 2021.

Ingold, T. ‘Earth, Sky, Wind and Weather’ in Being alive: Essays on movement, knowledge and description. London-New York: Routledge, 2011.

_____. The perception of the environment: Essays on livelihood, dwelling, and skill. London-New York: Routledge, 2000.

Juskus, R. ‘Sacrifice Zones: A Genealogy and Analysis of an Environmental Justice Concept’, Environmental Humanities, vol. 15, no. 1, March 2023: 3-24.

Lefebvre, M. ‘On Landscape in Narrative Cinema’, Canadian Journal of Film Studies, vol. 20, no. 1, March 2011: 61-78.

Lysen, F. and Pisters, P. ‘Introduction: The Smooth and the Striated’, Deleuze Studies, 6, 1, 2012: 1-5.

MacDonald, S. ‘The Ecocinema Experience’ in Ecocinema theory and practice, edited by S. Rust, S. Monani, and S. Cubitt. New York: Routledge, 2013: 17-42.

Malm, A. and Hornborg, A. ‘The geology of mankind? A critique of the Anthropocene narrative’, The Anthropocene Review, vol. 1, no. 1, April 2014: 62-69.

Neimanis, A. and Loewen Walker, R. ‘Weathering: Climate Change and the “Thick Time” ofTranscorporeality’, Hypatia, vol. 29, no. 3, Summer 2014: 558-575.

Plumwood, V. ‘The Concept of a Cultural Landscape: Nature, Culture and Agency in the Land’, Ethics & The Environment, vol. 11, no. 2, 2006: 115-150.

Rieser, S. and Rieser, K. ‘Poverty and Agency in Rural Noir Film’, Journal of Literary and Intermedial Crossings, 7, 22: e1-e-48.

Sitney, P.A. ‘Landscape in the cinema: the rhythms of the world and the camera’ in Natural beauty and the arts, edited by S. Kemal and I. Gaskell. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993: 103-126.

Valdés Olmos, T. ‘Ambivalence and Resistance in Contemporary Imaginations of US Capitalist Hinterlands’ in Planetary hinterlands: Extraction, abandonment and care, edited by Gupta, S. Nuttall, E. Peeren, and H. Stuit. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2024: 163-177.

_____. ‘De desillusie van de frontieridylle’, Armada 2, 75, 2022: 10-11.

Van Dooren, T. Flight ways: Life and loss at the edge of extinction. New York: Columbia University Press, 2014.

Wilkinson, A. ‘Nomadland turns American iconography inside out’, Vox.com, 19 February 2021: https://www.vox.com/22289457/nomadland-review-zhao-mcdormand-streaming-hulu.

Williston, B. ‘The Sublime Anthropocene’, Environmental Philosophy, vol. 13, no. 2, Fall 2016: 155-174.

[1] I would like to thank Toni Pape for his productive comments on an early version of this paper, and a big thank you to the organisers and participants of the annual ASCA workshop for their feedback. Last, I would like to thank the reviewers for their valuable suggestions.

[2] Ingold 2000 (orig. in 1989), p. 189.

[3] ‘Nomadland – Box Office’, The Numbers, Nash International Services: https://www.the-numbers.com/movie/Nomadland#tab=box-office(accessed on 30 August 2023).

[4] Holmes et. al. 2021; Wilkinson 2021.

[5] Dymussaga Miraviori 2022; Lindemann 2022; Grønstadt 2022; Rieser & Rieser 2022.

[6] Rieser & Rieser 2022.

[7] Alaimo 2016, p. 157.

[8] Braidotti 2011a, p. 22.

[9] Braidotti 2011b, pp. 3-4.

[10] Farrier 2019.

[11] Chakrabarty 2009.

[12] Williston 2015, p. 163.

[13] Dibley 2012, as cited in Farrier 2019, p. 7.

[14] Chakrabarty 2018.

[15] Farrier 2019, p. 52.

[16] Ibid., p. 9.

[17] Williston 2016.

[18] Farrier 2019, p. 9.

[19] Neimanis & Loewen Walker 2014, p. 559.

[20] Alaimo 2016, p. 157.

[21] Neimanis & Loewen Walker 2014, p. 561.

[22] Ibid., p. 571.

[23] Ibid., p. 570; Barad 2007.

[24] Farrier 2019, pp. 47-48.

[25] Valdés Olmos 2022.

[26] Rieser & Rieser 2022, p. 1n1; Grønstadt 2022.

[27] Deleuze 1989 (orig. in 1985), p. 7. I would like to thank the reviewer for bringing this connection to my attention.

[28] Ibid., p. 3.

[29] Ibid., p. xi.

[30] Val Plumwood as cited in Farrier 2019, p. 52.

[31] Juskus 2023, p. 16.

[32] Brudel 2017.

[33] Glissant 1997 (orig. in 1990), pp. 12-13.

[34] Ibid., p. 12.

[35] Deleuze & Gauttari 1987, p. 381.

[36] Lysen & Pisters, 2012.

[37] Ingold 2011, p. 115.

[38] See P. A. Sitney 1993.

[39] Van Dooren 2014, p. 27.

[40] Ibid., pp. 27-28.

[41] Lefebvre 2011, pp. 65-66; Berleant 2005.

[42] Ingold 2000 (orig. in 1989), p. 189.

[43] As cited in Gould 1987, p. 63.

[44] Cohen 2015, p. 107.

[45] Ibid., p. 79.

[46] Neimanis & Loewen Walker 2014, p. 561.

[47] Alaimo 2008, p. 238.

[48] Ibid., p. 435.

[49] Ibid., p. 571.

[50] Van Dooren 2014, p. 28.

[51] Neimanis & Loewen Walker 2014, p. 565.

[52] Braidotti 2011b, p. 3.

[53] Valdés Olmos 2024, p. 174.Tags:American cinema, Anthropocene, ecocinema, geology, nomadism, transcorporeality