David R. Cole

Abstract: There are 2.8 million objects housed by the Victoria and Albert Museum collection. Of these 2.8 million objects, a catalogue search revealed approximately 36 nomadic objects in the collection. This operation excludes objects that are made to imitate nomadic objects, and objects that may have been manufactured by sedentary culture to be distributed to nomadic peoples, such as the armour of nomadic warriors. Clearly, it is difficult to distinguish between objects made by sedentary processes, and those genuinely made by nomads for nomads, yet for the purposes of this presentation, it is true nonetheless that the overwhelming majority of objects in the V&A museum present a sedentary perspective/value system. This presentation wishes to explore the nature of the nomadic objects in the museum, and suggests that there is a connection between the nature of nomadic objects and the immense future societal changes necessary to reach net zero and survive the sixth great extinction event brought on by fossil fuels, global warming, and the Anthropocene.

Introduction -What is a nomadic object?

A nomadic object is an object made by nomadic people for their specific usage. Nomadic people are not tied to a specific place, or organizational focus that expands from a set point to encompass the surrounding spatial plane. Rather, nomadic people are bound to environmental and resource-based conditions, and are importantly able to move if these conditions adversely change – or move in cyclic migrations determined by the seasons. Hence, all nomadic objects must be able to be brought with the nomads when they move, and cannot exceed their carrying capacity – which includes the capacities of carrying animals that move in unison with the nomads such as camels, horses and yaks.

Nomadic objects tend to be small, lightweight, easily stored, and have personal and specific significance/use to the owner-nomad, who cannot accumulate an excess of these objects, as they would weigh him/her down when moving. One might ask what is the value of considering nomadic objects today, and how can this consideration make a difference to the Victoria & Albert Museum and its display of collections? I offer 3 points for reflection:

- We have developed sophisticated manufacturing techniques that are able to mass produce any object. This capacity has been enhanced by digital technology and advanced techniques such as 3D printing. The contemplation of nomadic objects sets up another dimension of the object in terms of the value and singular nature of the object. Every nomadic object is uniquely highly prized and cannot be endlessly (re)made.

- Most objects on display in museums such as the V&A determine a specific hierarchy and represent something static in that hierarchy. In contrast, nomadic objects are, whilst signifying a special and unique meaning for the owner, are not determinant of status, wealth in terms of possession, and/or the stasis of societal means of production. Rather, the nomadic objects point to the fluidity of social organization.

- In times of climate change, sometimes called, the Anthropocene, we need to revaluate what an object is and how it is used and stored in/by society. It is not enough to push green solutions to climate change, such as Electric Vehicles (EVs), Photovoltaic rooftops arrays (PVs), and/or decommissioning coal-fired powerplants. Rather, our relationship with objects must change. Rather than desiring a plethora of accumulated objects to decorate out homes and demonstrate out wealth and status, the objects that we make and use should be paired back to what is essential to live an ecologically responsible and sustainable life. This is where the nomadic objects and how they are displayed by museum such as the V&A London can make a difference in the fight to avert climate change disaster.

A: Tibetan nomadic objects in the V&A

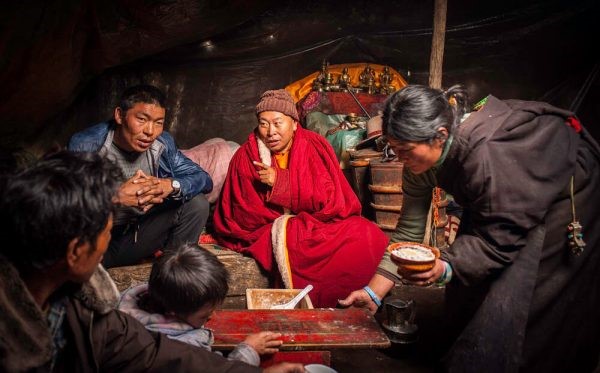

Breakfast at the nomad camp. Nangchen Gar area, Kham.

Amulet Box (ga’u)

Amulet Box

1800-1850 (made)

ARTIST/MAKER

Unknown

PLACE OF ORIGIN

Tibet (made)

This amulet case or ga’u of silver and coral, was used to hold rolled prayers and blessed or holy objects believed to protect the wearer from evil. This type of round amulet box was most popular among the nomads of north east Tibet. Such boxes were worn suspended on a strap or sash across the shoulder or around the waist when travelling.

Amulet Case (Ga’u)

early 19th century (made)

ARTIST/MAKER

Unknown

PLACE OF ORIGIN

Tibet (made)

This silver amulet case (or ga’u) would have been used to contain holy objects such as the relics of revered teachers, rolled prayers or other blessed objects. It was worn around the neck, and its contents protected the wearer from the harm caused by malevolent spirits. This type, worn mainly by women, is called a ‘kerima’ (mkhal ri ma), a name deriving from the shape of the box. (Khal means ‘kidney’.)

Teapot

18th century-19th century (made)

ARTIST/MAKER

Unknown

PLACE OF ORIGIN

Xigazê (made)

This type of teapot with its metal straps supporting a wooden body probably represents the oldest form of teapot in Tibet. In the last two centuries it was used mostly by nomad populations in north-east Tibet.

B: Central Asian nomadic objects in the V&A collection

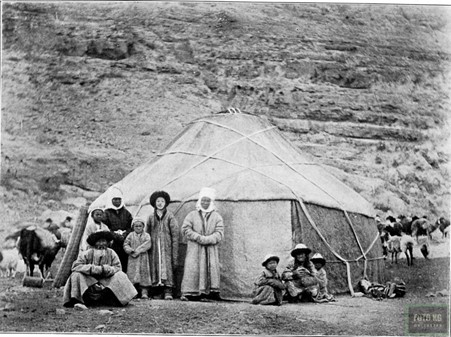

Nomad family in front of Yurt – a construction, which is designed to meet all needs of nomadic lifestyle. Photo: foto.kg

Chuval

1825-1875 (made)

ARTIST/MAKER

Unknown

PLACE OF ORIGIN

Central Asia (made)

Bags are important household articles for all nomadic people. They are used to transport possessions on pack animals when the community travels and are used for storage and decoration, and as something comfortable to lean against, when the community settles for a while and erects tents. The two sides of a bag, back and front, are called ‘faces’ and the one at the front is often decorated with knotted pile or with a woven design. This is the decorative pile face of a large storage bag probably made by the Salor people. Blue braid has been sewn along the lower edge to cover the raw edge – this is where the bag face was cut from the undecorated back panel. Small amounts of light purple silk have been used in the pile.

Bag Face

1800-1899 (made)

ARTIST/MAKER

Unknown

PLACE OF ORIGIN

Central Asia (made)

Bags are important household articles for all nomadic people. They are used to transport possessions on pack animals when the community travels and are used for storage and decoration, and as something comfortable to lean against, when the community settles for a while and erects tents. The two sides of a bag, back and front, are called ‘faces’ and the one at the front is often decorated with knotted pile or with a woven design.

This bag face, probably made by the Saryk tribal group, was deliberately woven so that it is wider along the lower edge to provide ample storage space with a narrower opening to give security.

Earring

1850-1880 (made)

PLACE OF ORIGIN

Turkestan (made)

Turkoman jewellery is one of the most distinctive and easily recognisable styles of traditional jewellery. It was worn by the nomadic tribes of Central Asia, in the present region of Turkmenistan and parts of northern Iran and Afghanistan. Although individual pieces rarely date from any earlier than the 19th century, many of the designs and symbols used are much older, often pre-Islamic in origin.

These earrings show many of the main characteristics of Turkoman jewellery, with their clean outline of pierced sheet silver, decorated only with applied wire and flat-cut cornelians, and numerous chain pendants ending in lozenges of sheet silver.

They were acquired in Turkestan in 1884-5, during an Anglo-Russian conference to define the north-west frontier of Afghanistan, and were given to the Museum in 1900.

Display of traditional nomad fabrics at the Nomad Games, Kyrgyzstan (2014)

C: Bedouin nomadic objects in the V&A

Bedouin tent in the Sahara

Nose ring

Nose Ring

1860-1870 (made)

ARTIST/MAKER

Unknown

PLACE OF ORIGIN

Syria (made)

The traditional jewellery of the Syrian region, which incorporated much of Palestine, Jordan and Lebanon as well as Syria itself in the 19th century, shows influences from a wide range of sources, reflecting Syria’s strong trading traditions and central location. The jewellery worn in towns, which is often Ottoman in style, is frequently very different from that worn by the nomadic Bedouin, whose characteristic silver jewellery is much better known today.

This object, looking like a tiny earring, was made to wear in the nostril of the nose. Nose rings are part of the traditional jewellery in the Syrian region, where they are called ‘shnaf’. They were mainly worn by Bedouin rather than urban women and their use almost certainly pre-dates the arrival of Islam. This example was bought for one shilling and sixpence, for a pair, at the International Exhibition, London, in 1872, as an example of traditional Syrian jewellery. Its name was recorded as ‘khyawr’, which may represent confusion with the local Arabic name for the typical, and commonly worn, cylindrical amulet case, khiyar, which means ‘cucumber’.

Pair of Anklets

1860-1870 (made)

ARTIST/MAKER

Unknown

PLACE OF ORIGIN

Syria (made)

Anklets, always worn in pairs, were part of the traditional dress of the nomadic Bedouin throughout the Syrian region in the 19th century. They were often very heavy, made of cast silver, and represented a major part of the wearer’s dowry. The name khulkhal is a generic Arabic name for anklets.

These, hollow and much lighter in weight, are similar to those worn on the Arabian peninsular. The tiny pellets inside them, which make a rattling sound as the wearer moves, were thought to have a protective function and to deter evil spirits. They were bought for four shillings and sixpence (the pair) at the International Exhibition, London, in 1872, as an example of traditional Syrian jewellery.

Necklace

Necklace

1860-1872 (made)

ARTIST/MAKER

Unknown

PLACE OF ORIGIN

Syria (made)

A torque is a stiff metal ring, usually open at the front, which is worn round the neck. They were originally made of twisted metal, as the name implies, and were used as indications of rank in Celtic times. They survived as part of the traditional jewellery in a number of places, including Syria.

The design of this torque, with different wires twisted together and linked by a hook at the front, and long chain pendants ending in coins, is typical of those made in Syria and Iraq. They were mainly worn by the nomadic Bedouin. This example was bought for the Museum for 16 shillings and 6 pence at the International Exhibition, London, 1872 as part of a large quantity of traditional Syrian jewellery.

D: Miscellaneous nomadic objects in the V&A collection

Nose Ring

20th century (made)

PLACE OF ORIGIN

Rajasthan (made)

A small nath in gold with crescent shape infill of decoration. It has a gold wire loop at the top with a hook and eye fastening on the left and a small four-petalled flower on the opposite side to the right. Beneath, the ring is filled with a curved gold plate decorated with a pattern of concentric lines of twisted wire and two rows of overlapping wirework rings dotted with regularly spaced single gold rings. The outer edge has a radiating gold fringe. A small ring is soldered on the left side of the back of the nose ring for a small chain (not surviving) to extend over to the wearer’s hair.

Clasp Knife

1750-1850 (made)

ARTIST/MAKER

Unknown

PLACE OF ORIGIN

Albania (made)

This knife formed part of the traditional jewellery of a Greek or Albanian woman.

Knives like this were a compulsory part of the dowry among the nomadic Sarakatsani herders, who wore them hanging from their belt on a long silver chain. This one is decorated with niello, called savati in Greek, which was used on many other kinds of Sarakatsani traditional jewellery as well.

It was acquired in Albania by Walter Child, a member of the famous family of London jewellers.