Jacquelyn K Shuman, Jennifer K Balch, Rebecca T Barnes, Philip E Higuera, Christopher I Roos, Dylan W Schwilk, E Natasha Stavros, Tirtha Banerjee, Megan M Bela, Jacob Bendix … Show more

PNAS Nexus, Volume 1, Issue 3, July 2022, https://doi.org/10.1093/pnasnexus/pgac115

Abstract

Fire is an integral component of ecosystems globally and a tool that humans have harnessed for millennia. Altered fire regimes are a fundamental cause and consequence of global change, impacting people and the biophysical systems on which they depend. As part of the newly emerging Anthropocene, marked by human-caused climate change and radical changes to ecosystems, fire danger is increasing, and fires are having increasingly devastating impacts on human health, infrastructure, and ecosystem services. Increasing fire danger is a vexing problem that requires deep transdisciplinary, trans-sector, and inclusive partnerships to address. Here, we outline barriers and opportunities in the next generation of fire science and provide guidance for investment in future research. We synthesize insights needed to better address the long-standing challenges of innovation across disciplines to (i) promote coordinated research efforts; (ii) embrace different ways of knowing and knowledge generation; (iii) promote exploration of fundamental science; (iv) capitalize on the “firehose” of data for societal benefit; and (v) integrate human and natural systems into models across multiple scales. Fire science is thus at a critical transitional moment. We need to shift from observation and modeled representations of varying components of climate, people, vegetation, and fire to more integrative and predictive approaches that support pathways toward mitigating and adapting to our increasingly flammable world, including the utilization of fire for human safety and benefit. Only through overcoming institutional silos and accessing knowledge across diverse communities can we effectively undertake research that improves outcomes in our more fiery future.

wildfire, climate change, resilience, wildland–urban interface, social–ecological systems

Issue Section:

Editor: Karen E Nelson

Significance Statement

Fires can be both useful to and supportive of human values, safe communities and ecosystems, and threatening to lives and livelihoods. Climate change, fire suppression, and living closer to the wildland–urban interface have helped create a global wildfire crisis. There is an urgent, ethical need to live more sustainably with fire. Applying existing scientific knowledge to support communities in addressing the wildfire crisis remains challenging. Fire has historically been studied from distinct disciplines, as an ecological process, a human hazard, or an engineering challenge. In isolation, connections among human and non-human aspects of fire are lost. We describe five ways to re-envision fire science and stimulate discovery that help communities better navigate our fiery future.

Introduction

Fire is a long-standing natural disturbance and a fundamental component of ecosystems globally (1). Fire is also an integral part of human existence (2), used by people to manage landscapes for millennia (3). As such, fire—or broadly biomass burning—can take on many forms: fires managed for human benefit or ecosystem health include prescribed or cultural burning, and response management beyond suppression; fires viewed as an immediate threat to human values are typically suppressed, and under increasingly extreme conditions have an increased chance of escaping suppression efforts. Fires can be ignited intentionally (e.g. prescribed or cultural burning and arson) or unintentionally (e.g. accidental human-caused or lightning-caused). They can happen in the wildlands and into human developed areas as in the wildland–urban interface (WUI). In the Anthropocene (The Anthropocene currently has no formal status in the Divisions of Geologic Time. https://pubs.usgs.gov/fs/2018/3054/fs20183054.pdf), the current era characterized by the profound influence of human impacts on planetary processes and the global environment (4), fires from lightning and unplanned human-related ignitions (including arson; henceforthreferenced as wildfires) result in increasingly negative impacts on economic (e.g. loss of structures and communities), public health (e.g. loss of life, air pollution, and water and soil contamination), and ecological aspects of society (e.g. shifts in vegetation and carbon storage) (5).

Recent decades have seen a substantial increase globally in the length of fire seasons (6), the time of year when conditions are conducive to sustain fire spread, increased area burned in many regions, and projected increases in human exposure and sensitivity to fire disasters (7–11). Fire seasons are occurring months earlier in Arctic and boreal regions (12). In the western United States, the area burned in the 21st century has nearly doubled compared to the late 20th century, enabled by warmer and drier conditions from anthropogenic climate change, resulting in dry, flammable vegetation (13). Fire activity in the 21st century is increasingly exceeding the range of historical variability characterizing boreal (14) and Rocky Mountain subalpine (15) forest ecosystems for millennia. Unprecedented fires in the Pantanal tropical wetland in South America (16) and ongoing peatland fires across tropical Asia (17) exemplify the global scope of recent fire extremes.

Shifts in wildfire patterns can come with increasingly negative human and ecological impacts. Globally, dangerous smoke levels are more common as a result of wildfires (9, 10, 18, 19). The 2019 to 2020 Australian wildfire season produced fires that were larger, more intense, and more numerous than in the historical record (20), injecting the largest amount of smoke into the stratosphere observed in the satellite era (21, 22) and impacting water supplies for millions of residents (23). While extreme fire events capture public attention and forest fire emissions continue to rise (24, 25), the ongoing decline of burned-area across some fire-dependent ecosystems might have equally large social and environmental impacts. Global burned area has decreased by approximately 25% over the last two decades, with the strongest decreases observed across fire-dependent tropical savanna ecosystems and attributed to human interactions (26). Decreases across these systems are important, as maintaining diverse wildfire patterns can be essential for biodiversity or achieving conservation goals (27).

Humans are fundamental drivers of changing wildfire activity via climate change, fire suppression, land development, and population growth (26, 28–30). Human-driven climate change is aggravating fire danger across western North America (13, 31, 32), Europe (33, 34), and Australia (35). Exacerbated by this increasing fire danger from heavy fuel loads and greater flammability from drought and tree mortality, human-caused ignitions increased wildfire occurrence and extended fire seasons within parts of the United States (28), and it is these human-caused wildfires that are most destructive to homes and property (36). Concurrent with these challenges is a growing recognition that Indigenous peoples have been living with fire as an essential Earth-system process (30). Although some Indigenous societies have lived in relatively low-density communities, others have lived at scales analogous to the modern wildland-urban interface for centuries, making Indigenous fire lessons relevant for the sustainability of post-industrial communities as well (e.g. (37)).

As wildfire danger increases, we are only beginning to understand longer-term postfire impacts. These include regeneration failure of vegetation (38, 39), changes to biodiversity through interactions with climate change, land use and biotic invasions (27), landslides and debris flows (40), contaminated water and soil (23, 41), and exposure to hazardous air quality for days to weeks in regions that can extend thousands of kilometers from smoke sources (9, 10, 19, 42). Increasing wildfire activity and associated negative impacts are expected to continue over the 21st century, as greenhouse gas emissions continue to rise (7, 43, 44).

The rapid pace of changing fire activity globally is a significant challenge to the scientific community, in both understanding and communicating change. Even the metrics we use to quantify “fire” come up short in many instances. For example, total area burned and ecological fire severity are useful for characterizing some key dimensions of fire, but often do not capture negative human impacts. For example, the 2021 Marshall Fire in Colorado, United States, was less than 2,500 hectares, but was more destructive, in terms of structures lost, than the two largest wildfires in recorded Colorado history, each of which burned approximately 80,000 hectares. The 2018 Mati Fire in Greece burned only 1,276 hectares, but destroyed or damaged 3,000 homes and was the second-deadliest weather-related disaster in Greece (11). While evidence suggests increasing aridity will lead to more burning (7, 32, 43, 45), the 2021 Marshall Fire and 2018 Mati Fire remind us that area burned is a poor indicator of the negative impacts of wildfires on the built environment.

Given the shifts in wildfire activity and its increasingly devastating impacts, the need to fund research and adopt policy to address fire-related challenges continues to grow. These challenges may be best addressed with coordinated proactive and collective governance through engagement of scientists, managers, policy-makers, and citizens (23). A recent United Nations’ report recognized extreme wildfires as a globally relevant crisis, highlighting the scope of this challenge (46). To address this crisis we need to recast how we study fire as an inherently transdisciplinary, convergent research domain to find solutions that cross academic, managerial, and social boundaries. As society urgently looks for strategies to mitigate the impacts of wildfires, the scientific community must deliver a coherent understanding of the diverse causes, impacts, management paths, and likely future of fire on Earth that considers the integrated relationships between humans and fire. Humans are not only affected by fire, but are also fundamental to its behavior and impact through our changes to the biosphere and our values, behaviors, and conceptions of risk.

The challenge of understanding the integrated role of humans and fire during the Anthropocene is an opportunity to catalyze the next generation of scientists and scientific discovery. It requires funding that develops collaborative, transdisciplinary science, dissolves disciplinary boundaries, and aligns research goals across traditional academic fields and ways of knowing. This represents an opportunity to build scientific practices that are respectful and inclusive of all, by creating spaces to share and co-produce knowledge between and among all stakeholders. Such practice demands multi-scale data collection and analysis to develop models that test our understanding, support safer communities, and provide long-term projections. By reinventing the training of scientists to reflect this transdisciplinary, multi-stakeholder, and data-driven approach, we can help revolutionize community practices and provide information needed by communities to be able to better live with fire—in all its forms—in our increasingly flammable world.

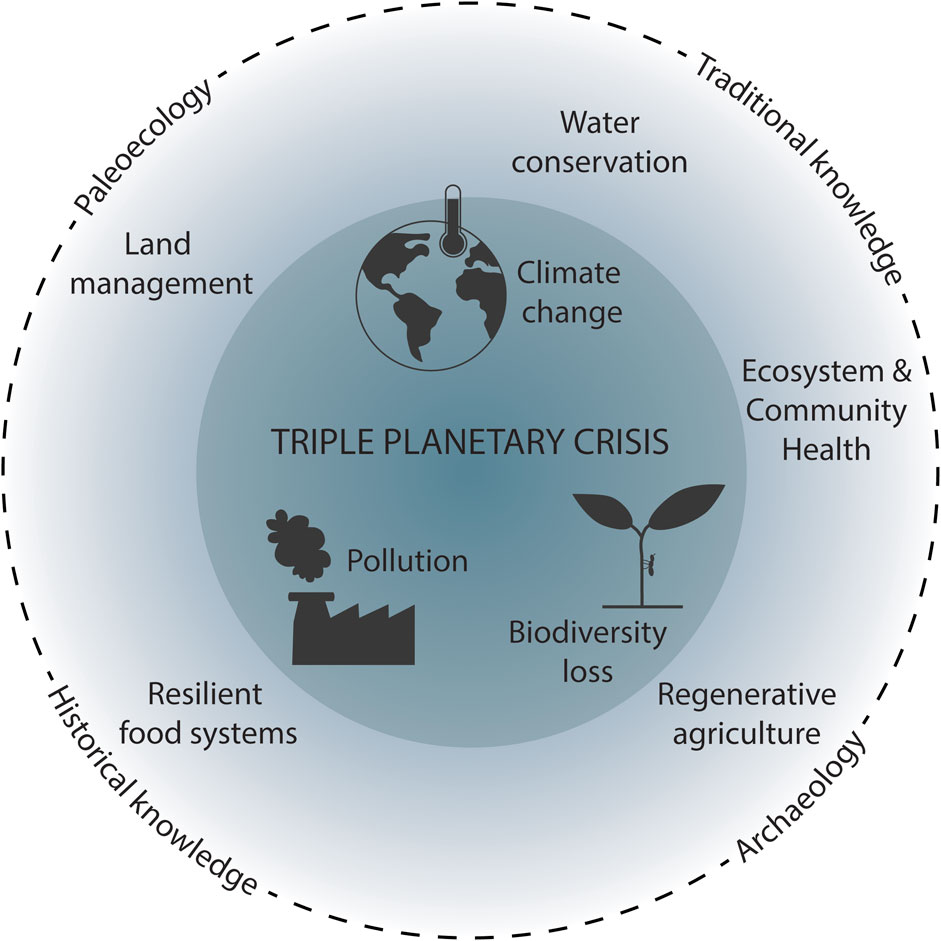

Here we identify five key challenges as a call to action to advance the study of fire as a fundamental aspect of life on Earth (Fig. 1).

- Integrate across disciplines by promoting coordination among physical, biological, and social sciences.

- Embrace different ways of knowing and knowledge generation to identify resilience pathways.

- Use fire as a lens to address fundamental science questions.

- Capitalize on the “firehose” of data to support community values.

- Develop coupled models that include human dimensions to better anticipate future fire.

Fig. 1.

We need a proactive fire research agenda to support human values and create safe communities as impacts from lightning and unplanned human-caused wildfires increase in the Anthropocene. Such an agenda will span multiple disciplines and translate understanding to application while answering fundamental science questions, incorporating diverse and inclusive partnerships for knowledge coproduction, capitalizing on the wealth of new and existing data, and developing models that integrate human dimensions and values.

These challenges are a synthesis of discussions of a group of mainly US-based researchers at the National Science Foundation’s Wildfire in the Biosphere workshop. The challenges of fire science extend beyond national borders, and our hope is that funding agencies, land stewards, and the larger fire science research community will join to address them. Within each call-to-action challenge we describe the nature of the challenge, address the social impacts, identify fundamental scientific advances necessary, and propose pathways to consider across communities as we address our place in a more fiery future (Table S1, Supplementary Material). Acting on these challenges will assist in better addressing the immediate impacts of fire, as well as postfire impacts (e.g. landslides and vegetation shifts). The focus on immediate needs is not meant to undermine the importance of longer-term impacts of fires, which in many ways are less understood, rather to highlight their urgency.

Discussion

1: Challenge: Integrate across disciplines by promoting coordination among physical, biological, and social sciences

Wildfire is a biophysical and social phenomenon, and thus its causes and societal impacts cannot be understood through any single disciplinary lens.

While studied for over a century, wildland fire science often remains siloed within disciplines such as forestry, ecology, anthropology, economics, engineering, atmospheric chemistry, physics, geosciences, and risk management. Within each silo, scientists often exclusively focus on fire from a specific perspective—fires as a human hazard, fire as a management tool, or fire as an ecological process. Collectively, we have deep knowledge about specific pieces of fire science; however, to move fire science forward and answer fundamental questions about drivers and impacts of fire, we must break out of traditional silos (e.g. institutional type, research focus, and academic vs. management) (47) to a more holistic and integrated approach across social (48), physical, and biological sciences, and including Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK) (49) (see Challenge 2).

Fire affects every part of the Earth system: the atmosphere, biosphere, hydrosphere, and lithosphere and plays a critical role in local to global water, carbon, nutrient, and climatic cycles by mediating the transfer of mass and energy at potentially large scales and in discrete pulses. Ecosystems and fire regimes are changing; we need to be prepared to anticipate tipping points and abrupt transitions to novel or alternative states. To fully understand the causes and consequences of shifting fire regimes, we must accept fire as a process with feedbacks between social and ecological systems while increasing respect among diverse communities (e.g. (50)). Rethinking collaborations across disciplines provides opportunities to determine shared values and goals (51) as well as new modes of practice that dismantle inequitable and exclusionary aspects of our disciplines (52). Team dynamics are particularly important in multidisciplinary collaborations given the varied experiences, expertise, and discipline-specific language used by team members. In many cases, these differences, in addition to the historical and systematic inequities within STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Math) fields (e.g. (53, 54)) have kept disciplines siloed and some groups excluded (55).

We need to build upon the adaptive, integrated knowledge, and “use-inspired” approaches, such as those put forth by Kyker-Snowman et al. (56) and Wall et al. (57), by including empiricists, modelers, practitioners, and domain experts from broad disciplines where they are involved at every stage of data collection, idea development, and model integration. In this approach, the two-way exchange of ideas is emphasized in order to effectively incorporate domain expertise and knowledge into models of systems that can not only improve understanding, but eventually move toward forecasting capability (see Challenge 5).

2: Challenge: Embrace different ways of knowing and knowledge generation to identify resilience pathways

Fire is an intrinsic part of what makes humans human, such that all humans from diverse groups and perspectives can provide valuable insights; thus co-produced knowledge is a prerequisite to innovation in fire science.

Given the urgent need to reduce wildfire disaster losses and to promote pathways to live sustainably with fire, it is critical to integrate knowledge from across disciplinary, organization, and community boundaries (58). Knowledge coproduction offers a model that identifies and produces science needed to drive change (59) through iterative, sustained engagement with key stakeholders (60). Specifically, development of mitigation tools and strategies enables social–ecological systems to transform from a resistance mindset to a resilience mindset (61).

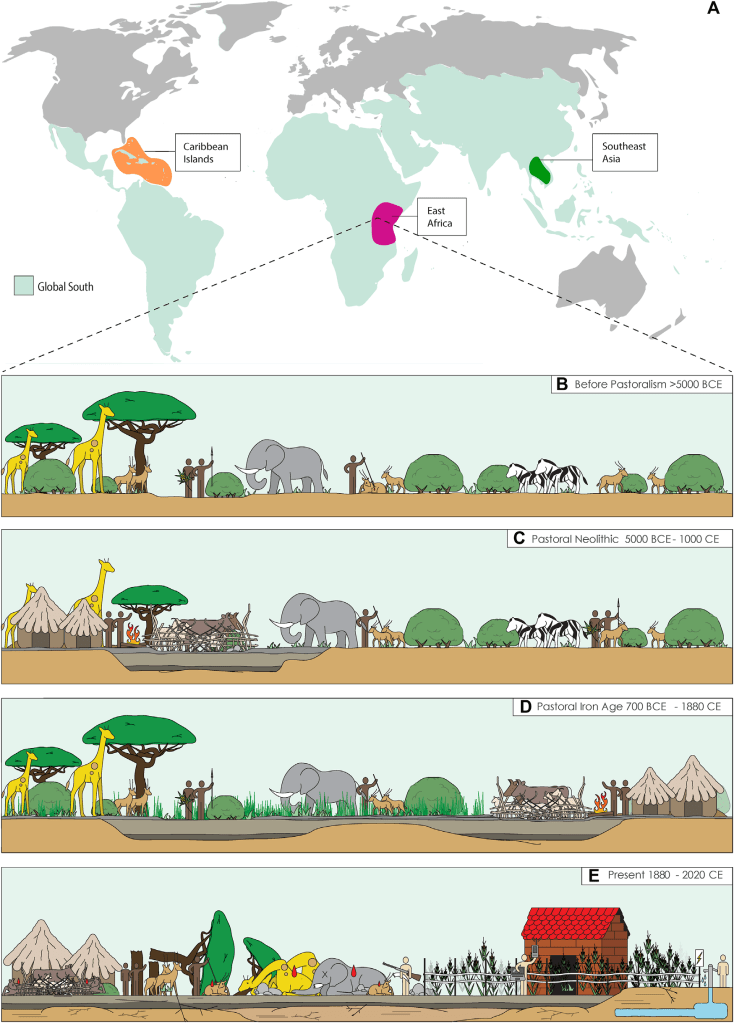

There exist millennia of knowledge by Indigenous peoples of Tribal Nations that hold Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK) of ancient burning practices (62–66) used to maintain healthy ecosystems. Indigenous and non-Indigenous place-based societies, such as traditional fire practitioners in Europe and elsewhere, have used fire to safeguard communities, promote desired resources, and support cultural lifeways for centuries to millennia (37, 49, 67–72). Working together, scientists from diverse cultural perspectives can co-define resilience across ecocultural landscapes (73), using this knowledge to identify perspectives of resilience to wildfire (72, 74). Our fire science community needs to work with diverse communities to determine what is valuable, generating needed information on risk scenarios and potential resilience pathways in the face of a changing climate, while upholding data principles that respect Tribal sovereignty and intellectual property (75).

We must accept fire as a social–ecological phenomenon that operates across multiple scales in space and time: fire acutely affects ecosystems, humans, and the biosphere; fire is a selective pressure and driver of ecological change; and humans, including various management practices, influence fire behavior and impacts. We need to understand where vulnerable communities are before wildfires occur, to build better, create defensible spaces around homes, reduce unintended human ignitions (e.g, downed power lines), and promote Indigenous management strategies and prescribed burning practices where they could mitigate disaster risk (37). Returning fire to landscapes and developing a culture of fire tailored to specific settings is increasingly seen as the most effective path forward. We repeatedly converged on the need for “sustainable” strategies for human communities to coexist with fire and smoke to become more aligned with TEK. Our authorship group, however, reflective of STEM disciplines more broadly, consists of non-Indigenous scientists. This situation emphasizes the need to prioritize collaboration with Indigenous scientists and community partners in developing ways to adapt to fire in a changing world.

It is critical to recognize the human role in using fire in the environment, and bring that into our understanding of adapting management for a more firey world. In turn, this can inform development of coupled models (see Challenge 5) representing fire as a human–biophysical phenomenon and can be used for management. To do so, we need to understand different value systems and develop metrics through co-production, thus collectively defining what success looks like for all stakeholders. This perspective provides scientific support for adaptive management and policy in the face of continuing human-caused change, including climate change. The resist–accept–direct (RAD) framework is explicitly designed to guide management through ecological transformations (76), a scenario increasingly likely with unprecedented climate change and enabled by fire. Because fire can catalyze social and ecological transformations, the RAD framework will be particularly useful for coming decades. Applying decision frameworks such as RAD requires incorporating human values, perceptions, and dynamism into fire management, within and beyond natural sciences (51, 77). Thus, the process itself offers potential for transdisciplinary innovation and inclusion of different ways of knowing (e.g. TEK) by requiring interdisciplinary engagement, including paleo scientists, ecologists, traditional knowledge holders, cultural anthropologists, archeologists, remote sensing experts, modelers, policy scientists, and community and government partners.

In addition to working across disciplines, we need to be aware of extant systems of oppression inherent in Western science (78). The lack of diversity among knowledge contributors in co-produced science and among scientists themselves fundamentally limits innovation, applicability, as well as being fundamentally unjust (79). Furthermore, as fire is a global ecosystem process, the research community should reflect a similar breadth in perspectives (80). However, fire science, not unlike many STEM fields, has problems with representation across all axes of identity, including gender, race, ethnicity, LGBTQA+, and disability (e.g. 81). For example, the majority of our authorship group work at US institutions, likely limiting the scope of our discussions. To change course, we need to interrogate our own practices and limit opportunities for bias. Providing clarity and transparency about and throughout decision-making processes (e.g. grants, job postings, and publications), training reviewers about bias, requiring the use of rubrics for all evaluations, and anonymizing application materials whenever possible, are all effective strategies to reduce gender and racial bias (82). Given the importance of representation, as a community we need to elevate a diverse group of role models (83), e.g. highlighting notable accomplishments of women-identifying fire scientists (84). To embrace diverse knowledge requires explicit consideration of equity in stakeholder participation and fire science recruitment and training from underrepresented backgrounds.

3: Challenge: Use fire as a lens to address fundamental science questions

We should use fire to answer fundamental scientific questions within and across physical, biological, and social sciences.

Fire is a ubiquitous and pervasive phenomenon, historically studied and tested in natural philosophy and scientific disciplines (85). It is also an ancient phenomenon with strong impacts on the Earth system and society across scales. Thus, fire is an excellent subject for asking basic questions in physical, biological, and social sciences. Here, we present three fundamental science areas that use fire to understand change: (a) ecology and evolutionary biology; (b) the evolution of Homo sapiens; and (c) social dynamics.

Fire is a catalyst for advances in ecology and evolutionary biology, providing a lens to examine how life organizes across scales and how organismal, biochemical, and physiological traits and fire-related strategies evolve. Consequently, fire ecology provides a framework for predicting effects of dramatic environmental changes on ecosystem function and biodiversity across spatial and temporal scales (27, 86), especially where fire may have previously not been present or has been absent for extended periods (e.g. (87)). Research is needed that targets the synergy of theoretical, experimental, and modeling approaches exploring the fundamental evolutionary processes of how organisms and communities function in dynamic and diverse fire environments. Fire allows researchers to investigate the fundamental and relative roles of traits and strategies across plant, animal, and microbial communities (27), and evaluate the influence of smoke on the function of airborne microbial communities (88), photosynthesis (89), and aquatic systems (90). A focus on fire has advanced evolutionary theory through the understanding of the evolution of plant traits and subsequent influence on the fire regime and selective environment, i.e. feedbacks (91). Fire–vegetation feedbacks may have driven the diversification and spread of flowering plants in the Cretaceous era (92, 93). This hypothesis builds upon processes observed at shorter time scales (e.g. the grass–fire cycle; (94)) and suggests flowering plants fueled fire that opened space in gymnosperm-dominated forests. This functional diversity can be parameterized into land surface models (see Challenge 5) by using phylogenetic lineage-based functional types to characterize vegetation, and could enhance the ecological realism of these models (95). Critically needed is an understanding of the reciprocal effects of fire and organismal life history characteristics and functional traits that characterize Earth’s fire regimes.

Fire provides an important lens through which we interpret major processes in human evolution. For example, the pyrophilic primate hypothesis (96) leverages observations from primatology (97) and functional generalization from other fire-forager species (98) to suggest that fire was critical for the evolution of larger-brained and big-bodied Homo erectus in sub-Saharan Africa by 1.9 million years ago. These populations relied upon fire-created environments and may have expanded burned areas from natural fire starts, all without the ability to start fires on their own. Fire-starting became a staple technology around 400,000 years ago (99), after which human ancestors could use fire in fundamentally new ways, including to further change their own selective environment (100). For example, at least some Neandertal (H. sapiens neandertalensis) groups in Europe used fire to intentionally change their local environment more than 100,000 years ago (101), and Middle Stone Age people (H. sapiens sapiens) in east Africa may have done the same shortly thereafter (3).

Fire illuminates social dynamics and can be a lens through which we examine fundamental issues in human societies, and even the dynamics of gendered knowledge (102). Specifically, fire questions convenient assumptions about population density and human–environmental impacts. For example, small populations of Maori hunter–gatherers irreversibly transformed non-fire-adapted South Island New Zealand plant communities when they arrived in the 13th century CE (103, 104), whereas large populations of Native American farmers at densities comparable to the modern WUI subtly changed patch size, burn area, and fire–climate relations in fire adapted pine forests over the past millennium (37). Similarly, in an ethnographic context much Aboriginal burning is done by women (105) and male uses of fire tend to have different purposes (106) with potential implications for varied social and environmental pressures on gendered fire uses, goals, and outcomes.

Answering fundamental fire science questions about evolutionary biology and the dynamics of human societies could help illuminate the role of humans in cross-scale pyrogeography. This is especially important in the Anthropocene as species, communities, and ecosystems arising from millennial-scale evolutionary processes respond to new disturbance regimes and novel ecosystem responses (107). Moreover, with increasing extreme fire behavior in many regions (16, 17, 35, 108), human societies must learn to live more sustainably with fire in the modern context (109). Fire is a catalyst for exploring fundamental questions and highlights the need for interagency fire-specific funding programs to support basic science. The direct benefits to society of fire research are well-acknowledged, but fire scientists are not organized as a broad community to argue for coordinated efforts to support basic science. Current fire-focused funding sources are usually limited to narrowly applied projects, while funders of basic science treat fire as a niche area. The result is duplicated efforts and competition for limited funds instead of coordination across an integrated fire science community.

4: Challenge: Capitalize on the “firehose” of data to support community values

We need funding to harness the data revolution and aid our understanding of fire.

The volume, type, and use of data now available to study fire in the biosphere is greater than ever before—a metaphorical “firehose” delivering vast amounts of information. Multidisciplinary science campaigns to study fire behavior and emissions are data intensive and essential for improving applications from local, regional, to global scales (e.g. ABoVE (110), MOYA (111), FASMEE (112), FIREX-AQ (113), MOYA/ZWAMPS (114), and WE-CAN (115)). Observation networks supported by the US National Science Foundation (e.g. NEON, National Ecological Observatory Network, 116) and the Smithsonian sponsored ForestGEO plots (117, 118) are uniquely valuable for the duration and intensity of data collection. Additionally, there are dozens of public satellites, and even more private ones, orbiting the planet collecting remote-sensing data related to pre-, active, and post-fire conditions and effects, thereby facilitating geospatial analysis from local, to regional, and global scales (119, 120). Terabases of genome-level molecular data on organisms spanning from microbes to plants and animals are readily generated (121). Finally, laboratory, field, and incident data exist like never before, where in the past there was limited availability.

While these data exist, there are challenges with the spatial and temporal frequency and coverage and duration of observations. Airborne flight campaigns cover a limited domain in space and time, while geostationary satellites provide high temporal resolution with relatively coarse spatial resolution and polar orbiting satellites provide higher spatial resolution, but lower temporal resolution. These tradeoffs in resolution and coverage lead to different data sources providing conflicting estimates of burned area (122, 123). We need investment in laboratory and field infrastructure for studying fire across a range of scales and scenarios (124) and continued work comparing and accounting for biases across existing data streams. We must develop infrastructure and support personnel to collect real-time observation data on prescribed or cultural fires (125) and wildfires in both wildlands and the wildland-urban interface across scales: from the scale of flames (i.e. centimeters and seconds) to airshed (kilometers and hours), to fire regimes (regions and decades).

Furthermore, many measures of fire processes and impacts are inferred from static datasets (126), while fires and their effects are inherently dynamic; collecting observations that capture these dynamics, such as the response of wind during a fire event, would greatly reduce uncertainties in forecasting the impacts of fire on social–ecological systems. For fast-paced, local processes like fire behavior and the movement of water and smoke, we need more high frequency observations from laboratory and field-based studies, such as the role of flame-generated buoyancy in fire spread (127), to update empirical relationships, some established by decades-old research and still used in models (128, 129). For centennial- to multi-millennial processes covering regions and continents, we need paleoclimate and paleoecological data sets that cover the variation in fire regimes (e.g. low severity vs. high severity) across ecoregions (130, 131).

We need technologies that collect data relevant for better understanding fire impacts on ecosystems and humans. New technology (e.g. ground-, air-, and space-borne lidars, radars, [hyperspectral] spectrometers, and [multispectral] radiometers) would enable measurements to help characterize surface and atmospheric structure and chemistry and better understand human land cover and land use in conjunction with fire impacts on air and water quality, ecosystems, and energy balance. We must use molecular techniques to capture the direct and indirect effects of soil heating on soil organic matter composition (132), belowground biological communities (133, 134), organism physiology (135), and ecosystem function processes (136). Finally, laboratory work can help better understand the mechanisms of heat transfer (137, 138), firebrand ember generation, behavior and transport (139, 140), atmospheric emissions (141), and transformation of fire plumes (115).

One challenge is that these data are not well-integrated for studying fire disturbance, as many were not specifically designed to examine the causes or effects of fire within an integrated social–ecological construct. For example, the use of diverse sets of multi-scale (tree, patch, local, and regional landscape) and multi-proxy records (pollen and charcoal, tree-ring fire scars, tree cohort analysis, inventories, photographic imagery, surveys, and simulation modeling) can be used to determine structure, tree-species composition and fire regimes (72, 142), and departures from historical ranges of variability (15, 143). However, this type of integrated historical data across a spatiotemporal continuum is not readily accessible to fire scientists, policy-makers, and communities. Current capabilities of remote sensing measurements of vegetation properties (144) are also not easily ingested as relevant information for more traditional fire models (145). Finally, there is limited access to global datasets of research-quality event-based data (24, 146–149), which is necessary to advance the understanding of human and biophysical processes of fire.

Many of these data are housed in disciplinary databases, such as the International Multiproxy Paleofire Database (150), which can be challenging for nonspecialists to access and use. We need to compile and merge these diverse data across spatial (m2 to Earth System) and temporal (milli-seconds to millennia) scales to support integration across disciplines, research groups, and agencies. Previous work provides an extensible framework for co-aligned airborne and field sampling to support ecological, microbiological, biogeochemical, and hydrological studies (112, 151). This work can be used to inform integration and coordination of data collection across platforms (field and remotely sensed), scales (flame to airshed), and systems (atmosphere, vegetation, soil, and geophysical), to establish a network that will produce long-term, open-access, and multi-disciplinary datasets related to fire science. This effort requires a reevaluation of how we collect data, ensuring we do so in ways that address key societal needs (e.g. aiding in human adaptability and maintenance of biodiversity). It highlights the need to coordinate across laboratory, field, and model-based research in designing future campaigns to develop, not only a common platform, but also a common language and coordinated data management across disciplines. Standardized data collection (e.g. observables, units, and so on) and protocols for quality control, archiving, and curation will be essential to merge existing datasets (90) and create new ones.

In support of increased utility, we need to establish and use common metadata standards and a community of practice for open algorithms and code, informed by the FAIR data principles making data and code Findable on the web, digitally Accessible, Interoperable among different computing systems, and thus Reusable for later analyses (152), and data literacy communities such as PyOpenSci (https://www.pyopensci.org/) and ROpenSci (https://ropensci.org/). Implementation of FAIR principles are complemented by the CARE (Collective benefit, Authority to control, Responsibility, and Ethics) principles that protect Indigenous sovereignty and intellectual property (75). This requires not only building coordination among federal agencies, but also with state, local, and Tribal governments and institutions. Such a community of practice, exemplary of ICON (Integrated, Collaborative, Open, Networked) science principles and practices (153), would facilitate more frequent collaborations across disciplines and lead to convergent research and data-intensive scientific discovery.

By compiling and merging diverse datasets, we can remove barriers to searching, discovering, and accessing information across disciplines, thereby accelerating scientific discovery to understand drivers and impacts of fire, helping support the development of more fire-resilient communities. There is considerable potential to harness this data revolution and explore cross-disciplinary research in the form of biomimicry adapted from long-term parallels from flora, fauna, and Indigenous peoples’ responses to fire (154), management planning with Potential Operational Delineations (PODs; (155)), and digital twins (156) that use coupled models including human dimensions (see Challenge 5) to adapt and test historical parallels and potential solutions for human communities and broader social–ecological systems.

5: Challenge: Develop coupled models that include human dimensions to better anticipate future fire

To better anticipate future fire activity and its impacts on and feedback with social–ecological systems, we must develop coupled models that integrate human- and non-human dimensions.

We need modeling frameworks that better represent fire in a social–ecological system, and that can be applied across multiple spatial and temporal scales spanning wildland–rural–urban gradients (8, 11, 20). Such frameworks should capture differences between managed and unmanaged fire as they relate to: preceding conditions, ignition sources (28), fire behavior and effects on ecosystems, humans, and the biosphere. Making this distinction between managed and unmanaged fire in modeling is essential to characterizing changes in the natural system due to the influence from human behavior (26). Fire has been a primary human tool in ecosystem management (30), and thus unraveling the variability in human–fire interactions over space and time (see Challenges 2 and 3) is necessary for understanding fire in the biosphere (26, 30, 69). There are multiple types of models that can benefit from better accounting for human interactions.

First, an improved forecasting system is needed to project both managed (e.g. prescribed burn and wildfire response) and unmanaged (i.e. wildfire) fire spread and smoke behavior, transport, and transformation (112). This can aid society’s strategic and managed response to fire in terms of community resilience (47, 74). Models of fire behavior and effects span spatial and temporal scales, but fundamental to each is the consideration of fuels, vegetation, and emissions. We must work to capture fuel heterogeneity, including the physiological dynamics that influence vegetation fuel loading (157), fuel moisture (158, 159), and the flammability of live and dead vegetation (160, 161). Fuel moisture and its variation in space and time have the capacity to alter fire behavior (162) and ecosystem vulnerability to wildfire (163). Currently, most models do not capture both these types of fuels and plant physiological dynamics, despite both influencing fire behavior, effects, and subsequently land surface recovery. Several wildfire propagation models exist ranging from empirical to process-based (127, 164), but they either entirely focus on wildlands (112, 164) or pertain to limited aspects to wildfire behavior in communities focusing on interactions among a group of structures (165) and not on the heterogeneous landscapes of the wildland-urban interface (166, 167). We are making significant advances in capturing the impacts of fire on winds during an event (164) as well as on local weather conditions (168, 169), which both have the capacity to alter fire behavior and path. Advances in analytical approaches are making it possible to model community vulnerability (170) and risk (171) from a fire propagation perspective while accounting for the interaction between structures (172). However, to date, we do not have consensus on a model to assess the survivability of individual structures from wildfire events, as available urban fire spread models are not designed for these communities and underestimate the fire spread rate in most cases (172). Developing such models is vital for determining how to manage wildfire risk at the community level.

Second, land surface models, which simulate the terrestrial energy, water, and carbon cycle, often represent fire occurrence and impacts, but omit key aspects or are parameterized in a simple manner (173). As such, there is a need to develop fire models within land surface models that integrate fire behavior and effects representative of the social–ecological environment within which humans interact with fires and subsequently influence impacts to terrestrial energy, water, and carbon cycles. The current generation of fire-enabled land surface models demonstrate that a lot of uncertainty is due to how the human impact on fires is currently characterized, and exemplifies the need for a better representation of human dimensions within global fire models (174–177). Relationships between people and fire are driven by interactions between the social environment in which humans act (e.g. livelihood system, land tenure, and land use), the physical environment (e.g. background fire regime, landscape patterns, and land management legacies), and the policy sphere. The current generation of fire-enabled land surface models are not able to represent fire in this social–ecological environment, and thus struggle to capture both historical changes in global fire occurrence (26), as well as how these changes have impacted ecosystems and society with sufficient regional variability in the timing and type of human impacts on fires (174, 175). Additionally, current land surface models do not represent mixed fuel types between natural vegetation, managed land, and the built-environment, which influence fire spread, characteristics, and impact directly. Land surface models rarely include the effects of fire on organic matter (i.e. pyrogenic organic matter production (178), or the nonlinear effects of repeated burning on soil carbon stocks (179)). As this likely plays an important role in the net carbon balance of wildfires (178), these omissions may amount to oversights in estimates of the impact of fires on carbon stocks (180). While land surface models often include simplified postfire vegetation dynamics for seed dispersal and tree seedling establishment, competition during succession, formation of large woody debris, and decomposition (e.g. (157, 181)), they exclude the influence humans have on these processes through land management.

Third, fire-enabled Earth system models, which seek to simulate the dynamic interactions and feedbacks between the atmosphere, oceans, cryosphere, lithosphere, and land surface (as such incorporate land surface models), use a simplistic representation of fire simulating aggregate burned area rather than the spread and perimeters of individual fires (182). This is a challenge for projecting the broad-scale impacts of fire on ecosystem resilience and functioning, because the temporal and spatial patterns of fire that vary as a function of managed vs. unmanaged fire, underpin whether and how ecosystems recover (183, 184). This further affects smoke emission speciation, formation, and behavior of greenhouse gases, aerosols, and secondary pollutants that affect the climate system (185, 186) through the absorption and scattering of solar radiation and land surface albedo changes. Our limited understanding is due in part to challenges related to representing this complexity and the resulting processes and impacts within and across interacting model grid cells.

There is a need for the infrastructure to implement and nest models across multiple scales, linking from fine to coarse temporal and spatial scales and including a two-way coupling to allow interaction between models. This would, for example, allow Earth system models to better capture changing vegetation and fuels through time, as modeled in land surface models; this in turn would help modelers capture finer-scale dynamics such as interactions between fire and weather and human interactions with individual fire events (e.g. suppression efforts). Reducing uncertainties across scales provides an opportunity to use data-assimilation to benchmark against multiple types of data at sites, for various scales, fires (prescribed/cultural and wild), and under variable conditions (see Challenge 4). Advanced analytics in machine learning and artificial intelligence can help ease computational complexity (187–189) in such an integrated framework.

Nested, coupled modeling frameworks that integrate across physical, biological, and social systems will not only enhance our understanding of the connections, interactions, and feedbacks among fire, humans, and the Earth system, but also enable adaptation and resilience planning if we create metrics to gauge the response of social–ecological systems to fire (e.g. (126, 190)). These metrics would include fire impacts on ecosystem services, human health, ecosystem health, and sustainable financing through policies on fire suppression, air and water quality, and infrastructure stability. Recent progress in understanding the characteristics of western United States community archetypes, their associated adaptation pathways, and the properties of fire-adapted communities (191, 192) should be explored across a diverse set of communities and used to inform such metrics.

Metrics for risk and resilience would need to be incorporated in these nested, coupled models that include human dimensions so that projections before, during, and after a fire could allow for informed decision-making. Risk includes not only the hazard, or potential hazard, of fire, but the exposure (directly by flame or indirectly from smoke) and vulnerability, as susceptibility, to be negatively impacted by the hazard; all of which are different for managed vs. unmanaged fire (20, 108, 143). Using models to quantify risk could, for example, guide planned management shifts from fire suppression to increased use of prescribed burning as an essential component for managing natural resources (143, 193, 194), but is currently challenging to implement due to smoke effects (195). Next-generation, integrated human–fire models are necessary to help managers both locally, those who use prescribed fire near communities (125, 196), and regionally or nationally, those who report emissions. While such a comprehensive framework would address the specific needs of different stakeholders and policy-makers, it would also be accessible and broadly comprehensible to the general public (e.g. fire paths forecast), similar to existing national warning systems for hurricanes and tornadoes. A focus on community resilience to wildfires expands the definition of risk beyond human impact to consider ecological and biological risk more holistically, as well as their role in a coupled social–ecological system. Integrating human behavior and decision dynamics into a nested modeling framework would allow for another dimension of feedback and interactions. Thus, integration of data and processes across scales within a nested, coupled modeling framework that incorporates human dimensions creates opportunities to both improve understanding of the dynamics that shape fire-prone systems and to better prepare society for a more resilient future with increased fire danger.

Conclusion

Now in the emerging era of the Anthropocene, where climate change and decoupling of historical land management have collided, society needs large-scale investment in the next generation of fire science to help us live more sustainably in our increasingly flammable world. Fire is a complex phenomenon that has profound effects on all elements of the biosphere and impacts human activities on a range of spatial and temporal scales. We need a proactive fire research agenda. Fire science has been reactive in that it responds to agency opportunities and conducts research in response to past fires. It is essential that we transition from this reactive stance to proactively thinking about tomorrow’s needs by acknowledging and anticipating future fire activity. This next generation of fire science will require significant new investment for a center that synthesizes across disciplines (Challenge 1), is diverse and inclusive (Challenge 2), innovative (Challenge 3), and data-driven (Challenge 4), while integrating coupled models that consider human dimensions and values (Challenge 5 ) (Fig. 1; Table S1, Supplementary Material).

One cause of current fragmentation within the United States is the narrow focus of major funding sources. Funding currently targets short-term goals, on small, single-Principal Investigator-led research, usually aimed at one aspect of fire science; it should target a holistic reimagination of our relationship with fire entirely, across academic, managerial, and social boundaries. This will create a broader and deeper understanding of the multifaceted nature of fire, with less focus on case studies and more focus on case integration. International projects funded by the European Commission have implemented a multi- and interdisciplinary approach, but can still be improved. Support for applied research will be most effective by aiming at both short- and long-term applications and solutions. There are active and prominent discussions on the need to fund fire science across government, local, and Indigenous entities that are all vested in understanding fire. These investments will be critical to advancing our ability to generate new insights into how we live more sustainably with fire. Fire will continue to have enormous societal and ecological impacts, and accelerate feedbacks with climate change over the coming decades. Understanding, mitigating, and managing those impacts will require addressing the presented five challenges to inform how we serve environmental and social justice by sustainably living and interacting with fire in our natural world.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank Kathy Bogan with CIRES Communications for the figure design and creation, and two anonymous reviewers for comments on an earlier version of the manuscript.

Funding

This material is based upon work supported by the National Center for Atmospheric Research, which is a major facility sponsored by the US National Science Foundation (NSF) under Cooperative Agreement No. 1852977. This manuscript is a product of discussions at the Wildfire in the Biosphere workshop held in May 2021 funded by the NSF through a contract to KnowInnovation. J.K.S. was supported as part of the Next Generation Ecosystem Experiments – Tropics, funded by the US Department of Energy, the Office of Science, the Office of Biological and Environmental Research, and by the NASA Arctic Boreal Vulnerability Experiment grant 80NSSC19M0107. R.T.B. was supported by the NSF grant DEB-1942068. P.E.H. was supported by the NSF grant DEB-1655121. J.K.B. and E.N.S. were supported by CIRES, the University of Colorado Boulder.

Authors’ Contributions

All authors—J.K.S., J.K.B., R.T.B, P.E.H, C.I.R, D.W.S, E.N.S., T.B., M.M.B., J.B., Sa.B., So.B., K.D.B, P.B., R.E.B, B.B, D.C., L.M.V.C., M.E.C., K.M.C., S.C., M.L.C., J.C.I., E.C., J.D.C., A.C., K.T.D., A.D., F.D., M.D, L.M.E., S.F., C.H.G., M.H., E.J.H, W.D.H., S.H., B.J.H., A.H., T.H., M.D.H, N.T.I., M.J., C.J., A.K.P., L.N.K., J.K., B.K., M.A.K., P.L., J.L., S.M.L.S., M.L., H.M., E.M., T.M., J.L.M., D.B.M, R.S.M., J.R.M, W.K.M., R.C.N., D.N., H.M.P., A.P., B.P., K.R., A.V.R., M.S., Fe.S., Fa.S., J.O.S., A.S.S., A.M.S.S., A.J.S., C.S., T.S., A.D.S., M.W.T., A.T., A.T.T., M.T., J.M.V., Y.W., T.W., S.Y., and X.Z. designed and performed the research; and J.K.S, J.K.B., R.T.B, P.E.H, C.I.R, D.W.S, and E.N.S. wrote the paper.

Data Availability

All data is included in the manuscript and/or supporting information.

Notes

Competing Interest: The authors declare no competing interest.

References

1. McLauchlan KK et al. 2020. Fire as a fundamental ecological process: research advances and frontiers. J Ecol. 108:2047–2069.

2. Medler MJ. 2011. Speculations about the effects of fire and lava flows on human evolution. Fire Ecol. 7:13–23.

3. Thompson JC et al. 2021. Early human impacts and ecosystem reorganization in southern-central Africa. Sci Adv. 7:eabf9776.

4. Crutzen PJ. 2002. Geology of mankind. Nature. 415:23–23.

5. Bowman DMJS et al. 2020. Vegetation fires in the Anthropocene. Nat Rev Earth Environ. 1:1–16.. DOI: 10.1038/s43017-020-0085-3.

6. Jolly WM et al. 2015. Climate-induced variations in global wildfire danger from 1979 to 2013. Nat Commun. 6:7537.

7. Bowman DMJS et al. 2017. Human exposure and sensitivity to globally extreme wildfire events. Nat Ecol Evol. 1:0058.

Google ScholarCrossrefWorldCat

8. Radeloff VC et al. 2018. Rapid growth of the US wildland-urban interface raises wildfire risk. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 115:3314–3319.

9. David LM et al. 2021. Could the exception become the rule? “Uncontrollable” air pollution events in the U.S. due to wildland fires. Environ Res Lett. 16:034029. DOI: 10.1088/1748-9326/abe1f3.

10. Augusto S et al. 2020. Population exposure to particulate-matter and related mortality due to the Portuguese wildfires in October 2017 driven by storm Ophelia. Environ Int. 144:106056.

11. Ganteaume A, Barbero R, Jappiot M, Maillé E. 2021. Understanding future changes to fires in southern Europe and their impacts on the wildland-urban interface. J. Saf Sci Resil. 2:20–29.

12. McCarty JL et al. 2021. Reviews and syntheses: Arctic fire regimes and emissions in the 21st century. Biogeosciences. 18:5053–5083.

13. Zhuang Y, Fu R, Santer BD, Dickinson RE, Hall A. 2021. Quantifying contributions of natural variability and anthropogenic forcings on increased fire weather risk over the western United States. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 118:e2111875118.

14. Kelly R et al. 2013. Recent burning of boreal forests exceeds fire regime limits of the past 10,000 years. PNAS. 110:13055–13060.

15. Higuera PE, Shuman BN, Wolf KD. 2021. Rocky Mountain subalpine forests now burning more than any time in recent millennia. PNAS. 118:e2103135118.

16. Libonati R, DaCamara CC, Peres LF, Sander de Carvalho LA, Garcia LC. 2020. Rescue Brazil’s burning Pantanal wetlands. Nature. 588:217–219.

17. Page SE, Hooijer A. 2016. In the line of fire: the peatlands of Southeast Asia. Philos Trans R Soc B Biol Sci. 371:20150176.

18. Kalashnikov DA, Schnell JL, Abatzoglou JT, Swain DL, Singh D. 2022. Increasing co-occurrence of fine particulate matter and ground-level ozone extremes in the western United States. Sci Adv. 8:eabi9386.

19. Requia WJ, Amini H, Mukherjee R, Gold DR, Schwartz JD. 2021. Health impacts of wildfire-related air pollution in Brazil: a nationwide study of more than 2 million hospital admissions between 2008 and 2018. Nat Commun. 12:6555.

20. Nolan RH et al. 2021. What do the Australian Black Summer Fires signify for the global fire crisis?. Fire. 4:97.

21. Hirsch E, Koren I. 2021. Record-breaking aerosol levels explained by smoke injection into the stratosphere. Science. 371:1269–1274.

22. Yu P et al. 2021. Persistent stratospheric warming due to 2019–2020 Australian wildfire smoke. Geophys Res Lett. 48:e2021GL092609.

23. Robinne F-N et al. 2021. Scientists’ warning on extreme wildfire risks to water supply. Hydrol Process. 35:e14086.

24. van Wees D et al. 2022. preprint Global biomass burning fuel consumption and emissions at 500-m spatial resolution based on the Global Fire Emissions Database (GFED). Geosci Model Dev Discuss. [preprint], https://doi.org/10.5194/gmd-2022-132, in review, 2022.

25. Zheng B et al. 2021. Increasing forest fire emissions despite the decline in global burned area. Sci Adv. 7:eabh2646.

26. Andela N et al. 2017. A human-driven decline in global burned area. Science. 356:1356–1362.

27. Kelly LT et al. 2020. Fire and biodiversity in the Anthropocene. Science. 370:eabb0355.

28. Balch JK et al. 2017. Human-started wildfires expand the fire niche across the United States. PNAS. 114:2946–2951.

29. Benjamin P, Freeborn H, Patrick J, Matt W, Morgan VJ. 2021. COVID-19 lockdowns drive decline in active fires in southeastern United States. PNAS. 118:e2105666118.

30. Bowman DMJS et al. 2011. The human dimension of fire regimes on Earth. J Biogeogr. 38:2223–2236.

31. Kirchmeier-Young MC, Gillett NP, Zwiers FW, Cannon AJ, Anslow FS. 2019. Attribution of the influence of human-induced climate change on an extreme fire season. Earths Fut. 7:2–10.

32. Abatzoglou JT, Williams AP. 2016. Impact of anthropogenic climate change on wildfire across western US forests. PNAS. 113:11770–11775.

33. Barbero R, Abatzoglou JT, Pimont F, Ruffault J, Curt T. 2020. Attributing increases in fire weather to anthropogenic climate change over France. Front Earth Sci. 8. DOI: 10.3389/feart.2020.00104.

34. Turco M et al. 2019. Climate drivers of the 2017 devastating fires in Portugal. Sci Rep. 9:13886.

35. Abram NJ et al. 2021. Connections of climate change and variability to large and extreme forest fires in southeast Australia. Commun Earth Environ. 2:1–17.

36. Mietkiewicz N et al. 2020. In the line of fire: consequences of human-ignited wildfires to homes in the U.S. (1992–2015). Fire. 3:50.

37. Roos CI et al. 2021. Native American fire management at an ancient wildland–urban interface in the Southwest United States. PNAS. 118:e2018733118.

38. Coop JD et al. 2020. Wildfire-driven forest conversion in western North American landscapes. Bioscience. 70:659–673.

39. Rammer W et al. 2021. Widespread regeneration failure in forests of Greater Yellowstone under scenarios of future climate and fire. Glob Change Biol. 27:4339–4351.

40. Thomas MA et al. 2021. Postwildfire soil-hydraulic recovery and the persistence of debris flow hazards. J Geophys Res Earth Surf. 126:e2021JF006091.

41. Campos I, Abrantes N. 2021. Forest fires as drivers of contamination of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons to the terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems. Curr Opin Environ Sci Health. 24:100293.

42. Burke M et al. 2021. The changing risk and burden of wildfire in the United States. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 118:e2011048118.

43. Abatzoglou JT et al. 2021. Projected increases in western US forest fire despite growing fuel constraints. Commun Earth Environ. 2:227.

44. Touma D, Stevenson S, Lehner F, Coats S. 2021. Human-driven greenhouse gas and aerosol emissions cause distinct regional impacts on extreme fire weather. Nat Commun. 12:212.

45. Turco M et al. 2017. On the key role of droughts in the dynamics of summer fires in Mediterranean Europe. Sci Rep. 7:81.

46. United Nations Environment Programme. 2022. “Spreading like Wildfire – The Rising Threat of Extraordinary Landscape Fires.”. Nairobi.

47. Smith AMS et al. 2016. The science of firescapes: achieving fire-resilient communities. Bioscience. 66:130–146.

48. Kuligowski E. 2017. Burning down the silos: integrating new perspectives from the social sciences into human behavior in fire research. Fire Mater. 41:389–411.

49. Lake FK et al. 2017. Returning Fire to the Land: Celebrating Traditional Knowledge and Fire. J For. 115:343–353.

50. Fischer AP et al. 2016. Wildfire risk as a socioecological pathology. Front Ecol Environ. 14:276–284.

51. Higuera PE et al. 2019. Integrating subjective and objective dimensions of resilience in fire-prone landscapes. Bioscience. 69:379–388.

52. Chaudhary VB, Berhe AA. 2020. Ten simple rules for building an antiracist lab. Plos Comput Biol. 16:e1008210.

53. Bernard RE, Cooperdock EHG. 2018. No progress on diversity in 40 years. Nat Geosci. 11:292–295.

54. Marín-Spiotta E et al. 2020. Hostile climates are barriers to diversifying the geosciencesIn: Advances in geosciences. Göttingen: Copernicus GmbH. p. 117–127.

55. Mattheis A, Nava L, Beltran M, West E 2020. Theory-practice divides and the persistent challenges of embedding tools for social justice in a STEM urban teacher residency program. Urban Educ. 0042085920963623.

56. Kyker-Snowman E et al. 2022. Increasing the spatial and temporal impact of ecological research: a roadmap for integrating a novel terrestrial process into an Earth system model. Glob Change Biol. 28:665–684.

57. Wall TU, McNie E, Garfin GM. 2017. Use-inspired science: making science usable by and useful to decision makers. Front Ecol Environ. 15:551–559.

58. Peek L, Tobin J, Adams RM, Wu H, Mathews MC. 2020. A framework for convergence research in the hazards and disaster field: the natural hazards engineering research infrastructure CONVERGE facility. Front Built Environ. 6. DOI: 10.3389/fbuil.2020.00110.

59. Norström AV et al. 2020. Principles for knowledge co-production in sustainability research. Nat Sustain. 3:182–190.

60. Bamzai-Dodson A, Cravens AE, Wade AA, McPherson RA. 2021. Engaging with stakeholders to produce actionable science: a framework and guidance. Weather Clim Soc. 13:1027–1041.

61. Béné C, Doyen L. 2018. From resistance to transformation: a generic metric of resilience through viability. Earths Fut. 6:979–996.

62. Kimmerer RW, Lake FK. 2001. The Role of Indigenous Burning in Land Management. J For. 99:36–41.

63. Marks-Block T, Tripp W. 2021. Facilitating Prescribed Fire in Northern California through Indigenous Governance and Interagency Partnerships. Fire. 4:37.

64. Mistry J, Bilbao BA, Berardi A. 2016. Community owned solutions for fire management in tropical ecosystems: case studies from Indigenous communities of South America. Philos Trans R Soc B Biol Sci. 371:20150174.

65. Bilbao B, Mistry J, Millán A, Berardi A. 2019. Sharing multiple perspectives on burning: towards a participatory and intercultural fire management policy in Venezuela, Brazil, and Guyana. Fire. 2:39.

66. Laris P, Caillault S, Dadashi S, Jo A. 2015. The human ecology and geography of burning in an unstable Savanna environment. J Ethnobiol. 35:111–139.

67. Huffman MR. 2013. The Many Elements of Traditional Fire Knowledge: Synthesis, Classification, and Aids to Cross-Cultural Problem Solving in Fire-Dependent Systems Around the World. Ecol Soc. 18:1–36.

68. Yibarbuk D et al. 2001. Fire ecology and Aboriginal land management in central Arnhem Land, northern Australia: a tradition of ecosystem management. J Biogeogr. 28:325–343.

69. Roos CI et al. 2016. Living on a flammable planet: interdisciplinary, cross-scalar and varied cultural lessons, prospects and challenges. Philos Trans R Soc B Biol Sci. 371:20150469

70. Coughlan MR. 2014. Farmers, flames, and forests: historical ecology of pastoral fire use and landscape change in the French Western Pyrenees, 1830–2011. For Ecol Manag. 312:55–66.

71. Seijo F, Gray R. 2012. Pre-industrial anthropogenic fire regimes in transition: the case of Spain and its implications for fire governance in Mediterranean type biomes. Hum Ecol Rev. 19:58–69.

72. Knight Clarke A et al. 2022. Land management explains major trends in forest structure and composition over the last millennium in California’s Klamath Mountains. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 119:e2116264119.

73. Copes-Gerbitz K, Hagerman S, Daniels L. 2021. Situating Indigenous knowledge for resilience in fire-dependent social-ecological systems. Ecol Soc. 26:25.

74. McWethy DB et al. 2019. Rethinking resilience to wildfire. Nat Sustain. 2:797–804.

75. Carroll SR et al. 2020. The CARE Principles for Indigenous Data Governance. Data Sci J. 19:43.

76. Schuurman GW et al. 2021. Navigating ecological transformation: Resist–Accept–Direct as a path to a new resource management paradigm. Bioscience. 72:16–29.. DOI: 10.1093/biosci/biab067. (December 20, 2021).

77. Crausbay SD et al. 2022. A science agenda to inform natural resource management decisions in an era of ecological transformation. Bioscience. 72:71–90.

78. Berhe AA et al. 2022. Scientists from historically excluded groups face a hostile obstacle course. Nat Geosci. 15:2–4.

79. Haacker R, Burt M, Vara M. 2022. Moving beyond the business case for diversity. EOS. 103. DOI: 10.1029/2022EO220080. (March 29, 2022).

80. Riley KL, Steelman T, Salicrup DRP, Brown S. 2020.; On the need for inclusivity and diversity in the wildland fire professions. In: Hood S.M., Drury S., Steelman T., Steffens R. editors. Proceedings of the Fire Continuum Conference – Preparing for the future of wildland fire, 2018 May 21-24; Missoula, MT. Fort Collins (CO): U.S. Department of Agriculture,. Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station. p. 2–7.

81. Macinnis-Ng C, Zhao X. 2022. Addressing gender inequities in forest science and research. Forests. 13:400.

82. Schneider B, Holmes MA. 2020. Science behind bias. In: Addressing gender bias in science and technology. ACS Symposium Series. Washington (DC): American Chemical Society, p. 51–71.

83. Etzkowitz H, Kemelgor C, Neuschatz M, Uzzi B, Alonzo J. 1994. The paradox of critical mass for women in science. Science. 266:51–54.

84. Smith AMS et al. 2018. Recognizing women leaders in fire science. Fire. 1:30.

85. Pyne SJ. 2016. Fire in the mind: changing understandings of fire in Western civilization. Philos Trans R Soc B Biol Sci. 371:20150166.

86. Pausas JG, Keeley JE, Schwilk DW. 2017. Flammability as an ecological and evolutionary driver. J Ecol. 105:289–297.

87. Worth JRP et al. 2017. Fire is a major driver of patterns of genetic diversity in two co-occurring Tasmanian palaeoendemic conifers. J Biogeogr. 44:1254–1267.

88. Kobziar LN et al. 2022. Wildland fire smoke alters the composition, diversity, and potential atmospheric function of microbial life in the aerobiome. ISME Commun. 2:1–9.

89. Hemes KS, Verfaillie J, Baldocchi DD. 2020. Wildfire-smoke aerosols lead to increased light use efficiency among agricultural and restored wetland land uses in California’s Central Valley. J Geophys Res Biogeosci. 125:e2019JG005380.

90. Robinne F-N, Hallema DW, Bladon KD, Buttle JM. 2020. Wildfire impacts on hydrologic ecosystem services in North American high-latitude forests: a scoping review. J Hydrol. 581:124360.

91. Laland K, Matthews B, Feldman MW. 2016. An introduction to niche construction theory. Evol Ecol. 30:191–202.

92. Bond WJ, Scott AC. 2010. Fire and the spread of flowering plants in the Cretaceous. New Phytol. 188:1137–1150.

93. Bond WJ, Midgley JJ. 2012. Fire and the angiosperm revolutions. Int J Plant Sci. 173:569–583.

94. D’Antonio CM, Vitousek PM. 1992. Biological invasions by exotic grasses, the grass/fire cycle, and global change. Annu Rev Ecol Syst. 23:63–87.

95. Griffith DM et al. 2020. Lineage-based functional types: characterising functional diversity to enhance the representation of ecological behaviour in land surface models. New Phytol. 228:15–23.

96. Parker CH, Keefe ER, Herzog NM, O’connell JF, Hawkes K. 2016. The pyrophilic primate hypothesis. Evol Anthropol Iss News Rev. 25:54–63.

97. Pruetz JD, Herzog NM. 2017. Savanna chimpanzees at Fongoli, Senegal, navigate a fire landscape. Curr Anthropol. 58:S337–S350.

98. Bonta M et al. 2017. Intentional fire-spreading by “Firehawk” raptors in northern Australia. J Ethnobiol. 37:700–718.

99. MacDonald K, Scherjon F, van Veen E, Vaesen K, Roebroeks W. 2021. Middle Pleistocene fire use: the first signal of widespread cultural diffusion in human evolution. PNAS. 118:e2101108118.

100. Laland KN, O’Brien MJ. 2010. Niche construction theory and archaeology. J Archaeol Method Theory. 17:303–322.

101. Roebroeks W et al. Landscape modification by Last Interglacial Neanderthals. Sci Adv. 7:eabj5567.

102. Eriksen C. 2014. Gender and wildfire: landscapes of uncertainty. London: Routledge.

103. McWethy DB et al. 2010. Rapid landscape transformation in South Island, New Zealand, following initial Polynesian settlement. PNAS. 107:21343–21348.

104. Perry GL, Wilmshurst JM, McGlone MS, McWethy DB, Whitlock C. 2012. Explaining fire driven landscape transformation during the Initial Burning Period of New Zealand’s prehistory. Glob Change Biol. 18:1609–1621.

105. Bird Bliege R, Bird DW, Codding BF, Parker CH, Jones JH. 2008. The “fire stick farming” hypothesis: Australian Aboriginal foraging strategies, biodiversity, and anthropogenic fire mosaics. PNAS. 105:14796–14801.

106. Bowman DMJS et al. 2016. Pyrodiversity is the coupling of biodiversity and fire regimes in food webs. Philos Trans R Soc B Biol Sci. 371:20150169

107. Pausas JG, Keeley JE. 2014. Abrupt climate-independent fire regime changes. Ecosystems. 17:1109–1120.

108. Iglesias V, Balch JK, Travis WR. 2022. US fires became larger, more frequent, and more widespread in the 2000s. Sci Adv. 8:eabc0020.

109. Moritz MA et al. 2014. Learning to coexist with wildfire. Nature. 515:58–66.

110. Miller CE et al. 2019. An overview of ABoVE airborne campaign data acquisitions and science opportunities. Environ Res Lett. 14:080201.

111. Barker PA et al. 2020. Airborne measurements of fire emission factors for African biomass burning sampled during the MOYA campaign. Atmos Chem Phys. 20:15443–15459.

112. Liu Y et al. 2019. Fire behaviour and smoke modelling: model improvement and measurement needs for next-generation smoke research and forecasting systems. Int J Wildland Fire. 28:570–588.

113. Wiggins EB et al. 2021. Reconciling Assumptions in Bottom-Up and Top-Down Approaches for Estimating Aerosol Emission Rates From Wildland Fires Using Observations From FIREX-AQ. J Geophys Res.: Atmos. 126:e2021JD035692.

114. MOYA/ZWAMPS Team. et al. . 2022. Isotopic signatures of methane emissions from tropical fires, agriculture and wetlands: the MOYA and ZWAMPS flights. Philos Trans R Soc Math Phys Eng Sci. 380:20210112.

115. Palm BB et al. 2020. Quantification of organic aerosol and brown carbon evolution in fresh wildfire plumes. PNAS. 117:29469–29477.

116. Nagy RC et al. 2021. Harnessing the NEON data revolution to advance open environmental science with a diverse and data-capable community. Ecosphere. 12:e03833.

117. Anderson-Teixeira KJ et al. 2015. CTFS-ForestGEO: a worldwide network monitoring forests in an era of global change. Glob Change Biol. 21:528–549.

118. Lutz JA, Larson AJ, Swanson ME. 2018. Advancing fire science with large forest plots and a long-term multidisciplinary approach. Fire. 1:5.

119. Gorelick N et al. 2017. Google Earth Engine: planetary-scale geospatial analysis for everyone. Remote Sens Environ. 202:18–27.

120. Wooster MJ et al. 2021. Satellite remote sensing of active fires: history and current status, applications and future requirements. Remote Sens Environ. 267:112694.

121. Jansson JK, Baker ES. 2016. A multi-omic future for microbiome studies. Nat. Microbiol. 1:1–3.

122. Gaveau DLA, Descals A, Salim MA, Sheil D, Sloan S. 2021. Refined burned-area mapping protocol using Sentinel-2 data increases estimate of 2019 Indonesian burning. Earth Syst Sci Data. 13:5353–5368.

123. Ramo R et al. 2021. African burned area and fire carbon emissions are strongly impacted by small fires undetected by coarse resolution satellite data. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 118:e2011160118.

124. Smith AMS et al. 2016. Towards a new paradigm in fire severity research using dose–response experiments. Int J Wildland Fire. 25:158–166.

125. Clements CB et al. 2015. Fire weather conditions and fire–atmosphere interactions observed during low-intensity prescribed fires – RxCADRE 2012. Int J Wildland Fire. 25:90–101.

126. Yabe T, Rao PSC, Ukkusuri SV, Cutter SL. 2022. Toward data-driven, dynamical complex systems approaches to disaster resilience. PNAS. 119:e2111997119.

127. Finney MA et al. 2015. Role of buoyant flame dynamics in wildfire spread. PNAS. 112:9833–9838.

128. Van Wagner CE. 1977. Conditions for the start and spread of crown fire. Can J For Res. 7:23–34.

129. Rothermel RC. 1972. A mathematical model for predicting fire spread in wildland fuels. Washington (DC): USDA Forest Service, Intermountain Forest and Range Experiment Station.

130. Davies GM, Gray A, Rein G, Legg CJ. 2013. Peat consumption and carbon loss due to smouldering wildfire in a temperate peatland. For Ecol Manag. 308:169–177.

131. Cobian-Iñiguez J et al. 2022. Wind effects on smoldering behavior of simulated wildland fuels. Combust Sci Technol. 0:1–18.

132. Miesel JR, Hockaday WC, Kolka RK, Townsend PA. 2015. Soil organic matter composition and quality across fire severity gradients in coniferous and deciduous forests of the southern boreal region. J Geophys Res Biogeosci. 120:1124–1141.

133. Whitman T et al. 2019. Soil bacterial and fungal response to wildfires in the Canadian boreal forest across a burn severity gradient. Soil Biol Biochem. 138:107571.

134. Revillini D et al. 2022. Microbiome-mediated response to pulse fire disturbance outweighs the effects of fire legacy on plant performance. New Phytol. 233:2071–2082.

135. Varner JM et al. 2021. Tree crown injury from wildland fires: causes, measurement and ecological and physiological consequences. New Phytol. 231:1676–1685.

136. Pellegrini AFA et al. 2021. Decadal changes in fire frequencies shift tree communities and functional traits. Nat Ecol Evol. 5:504–512.

137. Frankman D et al. 2012. Measurements of convective and radiative heating in wildland fires. Int J Wildland Fire. 22:157–167.

138. Aminfar A et al. 2020. Using background-oriented schlieren to visualize convection in a propagating wildland fire. Combust Sci Technol. 192:2259–2279.

139. Manzello SL et al. 2007. Firebrand generation from burning vegetation1. Int J Wildland Fire. 16:458–462.

140. Tohidi A, Kaye NB. 2017. Comprehensive wind tunnel experiments of lofting and downwind transport of non-combusting rod-like model firebrands during firebrand shower scenarios. Fire Saf J. 90:95–111.

141. Sekimoto K et al. 2018. High- and low-temperature pyrolysis profiles describe volatile organic compound emissions from western US wildfire fuels. Atmos Chem Phys. 18:9263–9281.

142. Hagmann RK et al. 2021. Evidence for widespread changes in the structure, composition, and fire regimes of western North American forests. Ecol Appl. 31:e02431.

143. Hessburg PF, Prichard SJ, Hagmann RK, Povak NA, Lake FK. 2021. Wildfire and climate change adaptation of western North American forests: a case for intentional management. Ecol Appl. 31:e02432.

144. Stavros EN et al. 2017. ISS observations offer insights into plant function. Nat Ecol Evol. 1:1–5.

145. Stavros EN et al. 2018. Use of imaging spectroscopy and LIDAR to characterize fuels for fire behavior prediction. Remote Sens Appl Soc Environ. 11:41–50.

146. Andela N et al. 2019. The Global Fire Atlas of individual fire size, duration, speed and direction. Earth Syst Sci Data. 11:529–552.

147. Balch JK et al. 2020. FIRED (Fire Events Delineation): an open, flexible algorithm and database of US fire events derived from the MODIS burned area product (2001–2019). Remote Sens. 12:3498.

148. St. Denis LA, Mietkiewicz NP, Short KC, Buckland M, Balch JK. 2020. All-hazards dataset mined from the US National Incident Management System 1999–2014. Sci Data. 7:64.

149. San-Miguel-Ayanz J et al. 2012. Comprehensive monitoring of wildfires in Europe: the European forest fire information system (EFFIS)In: Tiefenbacher J. editor. Approaches to managing disaster – assessing hazards, emergencies and disaster impacts. Vienna: IntechOpen.

150 Gross W, Morrill C, Wahl E. 2018. New advances at NOAA’s World Data Service for Paleoclimatology – promoting the FAIR principles. Past Glob Change Mag. 26:58–58.

151. Chadwick KD et al. 2020. Integrating airborne remote sensing and field campaigns for ecology and Earth system science. Methods Ecol Evol. 11:1492–1508.

152. Wilkinson MD et al. 2016. The FAIR Guiding Principles for scientific data management and stewardship. Sci Data. 3:160018.

153. Goldman AE, Emani SR, Pérez-Angel LC, Rodríguez-Ramos JA, Stegen JC. 2022. Integrated, Coordinated, Open, and Networked (ICON) science to advance the geosciences: introduction and synthesis of a special collection of commentary articles. Earth Space Sci. 9:e2021EA002099.

154. Smith AMS, Kolden CA, Bowman DMJS. 2018. Biomimicry can help humans to coexist sustainably with fire. Nat Ecol Evol. 2:1827–1829.

155. Greiner SM et al. 2020. Pre-season fire management planning: the use of Potential Operational Delineations to prepare for wildland fire events. Int J Wildland Fire. 30:170–178.

156. Bauer P, Stevens B, Hazeleger W. 2021. A digital twin of Earth for the green transition. Nat Clim Change. 11:80–83.

157. Hanan EJ, Kennedy MC, Ren J, Johnson MC, Smith AMS. 2022. Missing climate feedbacks in fire models: limitations and uncertainties in fuel loadings and the role of decomposition in fine fuel accumulation. J Adv Model Earth Syst. 14:e2021MS002818.

158. Talhelm AF, Smith AMS. 2018. Litter moisture adsorption is tied to tissue structure, chemistry, and energy concentration. Ecosphere. 9:e02198.

159. Nolan RH, Hedo J, Arteaga C, Sugai T, Resco de Dios V. 2018. Physiological drought responses improve predictions of live fuel moisture dynamics in a Mediterranean forest. Agric For Meteorol. 263:417–427.

160. Nolan RH et al. 2020. Linking forest flammability and plant vulnerability to drought. Forests. 11:779.

161. Ma W et al. 2021. Assessing climate change impacts on live fuel moisture and wildfire risk using a hydrodynamic vegetation model. Biogeosciences. 18:4005–4020.

162. Jolly WM, Johnson DM. 2018. Pyro-ecophysiology: shifting the paradigm of live wildland fuel research. Fire. 1:8.

163. Rao K, Williams AP, Diffenbaugh NS, Yebra M, Konings AG. 2022. Plant-water sensitivity regulates wildfire vulnerability. Nat Ecol Evol. 6:332–339.

164. Coen JL, Schroeder W. 2017. Coupled weather-fire modeling: from research to operational forecasting. Fire Manag Tod. 75:39–45.

165. McGrattan K et al. 2012. Computational fluid dynamics modelling of fire. Int J Fluid Dyn. 26:349–361.